Published in Peace & Change, Volume 39, Number 1, January 2014, pp. 73-100

pdf of published article

Brief summary of dilemma actions and application to the Freedom Flotilla, in Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns, 2014, pp. 129-130, 170-172

When nonviolent activists design an action that poses a dilemma for opponents - for example whether to allow protesters to achieve their objective or to use force against them with consequent bad publicity - this is called a dilemma action. These sorts of actions have been discussed among activists and in activist writings but not systematically analyzed. We present a preliminary classification of different aspects of dilemma actions and apply it to three case studies: the 1930 salt march in India, a jail-in used in the Norwegian total resistance movement in the 1980s, and the freedom flotillas to Gaza in 2010 and 2011. In addition to defining what is the core of a dilemma action, we identify five factors that can make the dilemma more difficult for opponents to "solve." Dilemma actions derive some of their effectiveness from careful planning and creativity that push opponents in unaccustomed directions.

___________________________________

In 1967, during the Indochinese war, a US Quaker activist group organized a ship to deliver medical supplies to North Vietnam. The US government was placed in a dilemma: either allow the ship to deliver goods to its then enemy or use force to stop it, causing adverse publicity from stopping humanitarian action.

US nonviolent activist George Lakey used this example in his book Powerful Peacemaking to illustrate what he called "dilemma demonstrations."[1] He presented the dilemma as between two options for authorities: either let protesters continue with their demonstration, which would achieve an immediate goal, including educating the public, or use force to stop them, thereby revealing their harsh side and generating popular concern.

Dilemma actions have been discussed within activist circles, with occasional commentary in print. For example, the manual Nonviolent Struggle: 50 Crucial Points, written by Otpor activists involved in the struggle that brought down Slobodan Milosevic's government in Serbia in 2000, includes a two-page treatment of dilemma actions.[2] Their formulation is slightly different from Lakey's. They recommend identifying a government policy that conflicts with widely held beliefs and then designing an action that requires the government to choose either doing nothing or applying sanctions that violate the widely held beliefs. For example, the policy might be censorship, the widely held belief be that people should have access to information and the action be publishing Buddhist literature. "In either case the government loses, because doing nothing means allowing its policies and laws to be disobeyed, and reacting with sanctions means violating what most of the population feels are important beliefs and values."[3] The idea of appealing to widely held beliefs is not unique to Otpor: it was also emphasized by Bill Moyer in his writings about how social movements should strategize to win.[4]

Philippe Duhamel gives this description:

A dilemma demonstration is a tactical framework that puts power holders in a dilemma: if the action is allowed to go forward, it accomplishes something worthwhile related to the issue or position being asserted. If the power holders repress the action, they put themselves in a bad light, and the public is educated about the issue or position.[5]

Duhamel provides a comprehensive analysis of a dilemma action in 2001 in Ottawa, Canada, that was part of a citizens' campaign against the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas.

Dilemma actions are worthy of interest for both activists and academics. For activists, they provide an approach for increasing the effectiveness of nonviolent-action strategies. Knowing more about the dynamics of dilemma actions and their core features can enable activists to design their actions to pose difficult dilemmas to opponents, leading opponents to make inferior decisions or waste their efforts preparing for several possible responses. Below we will show that activists and scholars have sometimes talked about an important element of a particular dilemma action as if it was a core feature of the phenomenon of dilemma actions. In our analysis we list five factors that can make a dilemma more acute but are not core features of dilemma actions generally. Being aware that elements can be important without being central ought to make it easier for activists to conceptualize a wider variety of dilemma actions. At the same time, understanding the range of elements that can contribute to a dilemma can inspire activists. Nonviolence scholars ought to pay attention to themes and concepts that activists discuss and care about; that dilemma actions have not been more carefully analyzed before is a major gap in nonviolence theory. In addition, understanding dilemma actions within nonviolent-action arenas has the potential to give peace researchers insights into dealing with or posing dilemmas in other domains, such as negotiations, peace-building, or ways to challenge structural violence.

Many dilemma actions derive their potency from the possibility that force used against nonviolent protesters may generate a backlash. The dynamics of this backlash were first conceptualized by Richard Gregg, based on his observations of campaigns led by Gandhi in India.[6] Gregg coined the expression "moral jiu-jitsu": violence by the authorities rebounds against them like the force of an opponent in the sport of jiu-jitsu. Gregg attributed moral jiu-jitsu to psychological effects on attackers, though Weber later showed that the effect was due to influences on third parties, not on the police who beat protesters.[7] Nonviolence scholar Gene Sharp generalized Gregg's concept to include social and political processes for generating a backlash when authorities use force against peaceful protesters, calling this "political jiu-jitsu." Sharp used examples such as the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa in 1960 and the bloody Sunday killings in Russia in 1905.[8] Brian Martin has developed the backfire model, a generalization of Sharp's political jiu-jitsu that includes methods used by attackers to reduce outrage from their actions and counter-methods by which protesters can increase outrage.[9] In all these frameworks, a jiu-jitsu or backfire effect is less likely when protesters use violence, because more observers will judge that violence by the authorities is legitimate.

A question then arises: is every nonviolent action a dilemma action? After all, authorities always have a choice between allowing the action to proceed and using force to stop it. Nonviolent action does not pose a dilemma to authorities in at least two circumstances. The first is when the action can be ignored or tolerated because it has little credibility, only a small audience or is considered harmless. The second is when countermeasures such as repression do not generate popular concern. This can happen when authorities inhibit outrage, for example by operating in secret.

A dilemma action is therefore a special kind of action in which the choices for the opponent are not easy, as assessed at the time or in hindsight. A conventional expression of social concern, such as an antiwar rally on Hiroshima Day in a liberal democracy, poses no dilemma: authorities may tolerate or even facilitate the event because it poses little threat to vested interests, whereas banning it would arouse antagonism. Some forms of civil disobedience, such as ploughshares actions involving damaging military equipment, also pose no dilemma, because authorities know exactly what to do: arrest the activists, who willingly surrender to police. Nevertheless, it is more useful to think of dilemma actions as a matter of degree rather than dichotomously present or absent. In the ideal type of a dilemma action, the optimal choice for the opponent is not obvious to anyone.

The concept of dilemma, namely a difficult choice between options, each of which has advantages and disadvantages, is generic. However, there appears not to be any standard classification of types of dilemmas. In philosophy, there is discussion of moral dilemmas, which, while of limited direct applicability to dilemma actions, raises some relevant concepts.[10]Many nonviolent activists are motivated by moral considerations, so it is useful to survey what philosophers say about moral dilemmas.

The moral dilemmas most commonly analyzed are faced by individuals, who must make a choice within a single moral framework. Philosophers disagree about whether moral systems should allow dilemmas, or whether every set of choices has a unique correct answer. However, these matters are irrelevant for the practicalities of most dilemmas involving nonviolent action, because they are multi-person interactions, and the different participants may be, and often are, operating with different moral frameworks. Nevertheless it is worth exploring what philosophers say about dilemmas, in order to see whether there are any insights relevant to understanding dilemma actions.

Philosophers have analyzed moral dilemmas imposed by others where an individual has to decide what to do, a famous example being Sophie's Choice , in which Nazis tell a mother to choose which one of her two children will live; if she refuses to choose, both will be killed.[11] However, the perspective of those constructing dilemmas to be imposed on others is lacking from the literature. This also brings up another point of difference. Philosophers have analyzed dilemmas imposed by "bad guys" such as Nazis. Nonviolent activists, in opposing repression and injustice, might be seen as the "good guys," at least by many outside observers, a configuration not addressed in studies of moral dilemmas.

James Jasper, a sociologist and social movement researcher, offers another approach to dilemmas. Using the concept of games (but being critical of game theory), he emphasizes the complexities of problems people face in everyday life, and the importance of the interactions and relationships between everyone involved in the dilemma, rather than seeking solutions to the problems.[12] Like philosophers, Jasper distinguishes dilemmas involving individuals (single players) from those involving "compound players" such as organizations. Another term used by Jasper is the "arena" where a dilemma takes place. The concepts of single player, compound player and arena are useful for studying dilemma actions, as is Jasper's emphasis on the question of who initiates the engagement.

Jasper lists a wide range of dilemmas, such as whether to think about immediate objectives or long-term goals[13] or whether to treat followers as resources or as players.[14] However, he does not address the question of trying to impose dilemmas on others.

Game theory provides another approach to dilemmas. The most well-known configuration is the prisoner's dilemma, which is an interactive scenario: a prisoner's payoff depends on the choice made by the other prisoner as well the prisoner's own choice. The configuration of a dilemma action is different, in that activists intend their opponent to experience a dilemma, though sometimes activists face dilemmas too. In game theory, dilemma actions can be accommodated by having payoffs in two different domains that cannot be combined quantitatively. However, not allowing quantitative combination negates most of the mathematical apparatus of game theory.

To illustrate the potential complexity of dilemmas, it is useful to divide them into types. We propose a framework with three domains and multiple types within each domain.

Moral dilemmas

Ideological dilemmas

Interpersonal dilemmas (involving, for example, friendship)

Intra-organizational dilemmas (involving relationships between groups within organizations)

Inter-organizational dilemmas (involving relationships between different organizations)

Political dilemmas

Economic dilemmas

Social dilemmas

A solely moral dilemma could involve a choice between two moral principles, for example between protecting a child and protecting the mother (as in a dangerous birth). An inter-organizational dilemma might involve whether to placate one of two rival groups in a coalition when this is highly likely to antagonize the other group.

Then there are mixed dilemmas involving combinations of different types of dilemmas, especially between different domains. A moral-interpersonal dilemma could involve a choice between a moral principle and a friend, for example whether to support a friend for a position over someone who is better qualified. An ideological-economic dilemma might involve a choice between a belief system and economic interests, for example whether to support subsidies for an industry that clash with a belief in free markets.

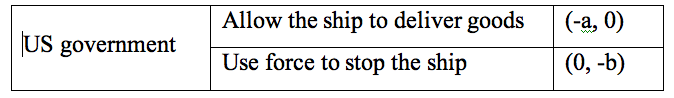

In game theory formalism, a dilemma can be presented as in Table 1, which illustrates a political dilemma for the US government. Allowing the ship to deliver goods to North Vietnam is a political loss of magnitude a, but there are no adverse consequences from using force (-a, 0); using force to stop the ship means no political consequences from a delivery, but there is a political loss of magnitude b from adverse publicity (0, -b).

Table 1 A political dilemma for the US government

The dilemma arises because there is no simple or commonly agreed way of amalgamating the two types of payoffs to a single measure. Sometimes the dilemma is posed to a single opponent, for example a political leader, who is torn between ordering the use of force or not; in many cases, the dilemma is posed to a compound player, such as a committee in which different individuals have different preferences. Often, there are both short term and long term aspects of the dilemma to be taken into consideration for all sides.

With this background, we can lay out the features of a dilemma action. First, the other side must have choices. Second, the outcomes of different choices have mixtures of benefits and costs that are qualitatively different or in different domains. No choice by the opponent can be obviously better by all criteria or according to all decision-makers.

Uncertainty is probably involved in most cases. No one knows for sure exactly what will happen following a choice of action, or perhaps there are disagreements about what will happen. However, strategy is about making decisions under uncertainty, taking into account the relative likelihood of different outcomes. Uncertainty does not mean absence of knowledge: there can be knowledge about what things are more likely to occur, and nonviolent activists planning a dilemma action are likely to benefit from thinking along these lines. First, they could consider possible opponent responses and assess the likely effects of those responses. Then they could choose a different action, modify their chosen action or make preparations to increase the benefits to the activists if the opponents make their best response. If opponents make a second-best choice, the benefits to the activists are even greater.

Taking Jasper's concepts of players, arenas and initiatives as well as the theoretical background of domains as our starting point, we developed a set of questions to apply to potential case studies of dilemma actions. The intention with these questions is to be able to compare the case studies and find elements that contribute to the dilemma without being core features.

Who are the players?

Who initiates the engagement?

Which arenas are available?

Which arena do the activists try to play on?

What types of dilemmas are involved?

What choices does the opponent have in the short and long run?

What are the consequences of the action in the short and long run?

How does the dilemma action differ from other possible actions? Specifically, how does the choice or design of the dilemma action affect the attractiveness of the opponent's responses?

In the following sections, we examine three nonviolent actions with characteristics of a dilemma action: the 1930 salt march in India, a humorous intervention in the Norwegian total resistance campaign in the 1980s, and the 2010 and 2011 freedom flotillas to Gaza. In selecting these cases out of many possible ones, we aimed for diversity in terms of time, place, numbers involved and context. The three case studies, spanning more than 80 years, include an anti-colonial struggle, a national case in a democratic setting, and an international solidarity action. We also picked cases that illustrate that what might seem to be a core feature in a particular case (for instance the constructive element in the Freedom Flotilla or the surprise element in the jail-in) turns out to be absent in other cases, meaning that it cannot be a core feature of all dilemma actions. Each action was one episode in a longer-running campaign. We describe the action and attempt to answer the questions above. Afterwards we identify the characteristics of dilemma actions, and in the conclusion we spell out the implications for understanding dilemma actions and their relevance in nonviolence campaigns.

In 1930, the Indian independence movement faced many challenges. Gandhi was the acknowledged leader, but there were critics on the left and, more importantly, the population was splintered by caste, class, religion and sex, so it was difficult to find a way to unite Indians against the British colonial rulers.

Gandhi came up with the idea of a campaign against British salt laws. The salt tax was a minor matter in the scheme of British rule, but Gandhi realized it had the potential of mobilizing Indians from all walks of life. The plan was to march to the sea with the intention of undertaking civil disobedience by making salt from seawater. The march was an elaborate affair, designed to maximize popular support through a slow build-up. Starting in March, the marchers took 24 days to reach the Dandi on the coast. Stopping at towns along the way, Gandhi gave talks and the marchers gained more support and publicity.[15]

The British rulers were faced by a dilemma: arrest Gandhi and other movement leaders as the march proceeded, or wait until they had broken the law. Arresting Gandhi early in the march had the advantage of restricting the mobilization of support the march was engendering; waiting until later meant the campaign achieved many of its goals. However, arresting Gandhi early could be counterproductive, because it contravened the rule of law: Gandhi, merely by walking and talking, did nothing illegal. British rule maintained much of its legitimacy, in India and Britain, from its adherence to its own norms. Because Gandhi was so famous, illegitimate action against him would inflame public opinion far beyond arresting a lesser figure. Furthermore, the issue of the salt laws seemed trivial at one level - therefore making arrests over violating the laws seem excessive - and, at another level, a powerful basis for mobilization, because it was so easy to understand the issues and participate in civil disobedience.

The salt march thus was a dilemma action, though this concept did not exist at the time. A nationalist newspaper clearly expressed the dilemma:

To arrest Gandhi is to set fire to the whole of India. Not to arrest him is to allow him to set the prairie on fire. To arrest Gandhi is to court a war. Not to arrest him is to confess defeat before the war is begun ... In either case, Government stands to lose, and Gandhi stands to gain. ... That is because Gandhi's cause is righteous and the Government's is not.[16]

A history of the independence struggle describes the situation this way:

The Government was placed in a classic "damned if you do, damned if you don't" fix, i.e., if it did not suppress a movement that brazenly defied its laws, its administrative authority would be seen to be undermined and its control would be shown to be weak, and if it did suppress it, it would be seen as a brutal, anti-people administration that used violence on non-violent agitators.[17]

J. C. Kumarappa expressed the problem facing the British:

Dharasana raid was decided upon not to get salt, which was only the means. Our expectations was that the Government would open fire on unarmed crowds . ... Our primary object was to show the world at large the fangs and claws of the Government in all its ugliness and ferocity. In this we have succeeded beyond measure.[18]

How to respond to the salt march was experienced as a moral dilemma by the viceroy, Lord Edward Irwin. In letters written at the time, he expressed his difficulty in deciding whether to arrest Gandhi.[19]

John Court Curry, a British police officer, encountered Gandhi in both 1919 and 1930. So great was the tension he experienced in responding to nonviolent action that he felt "severe physical nausea."

From the beginning I had strongly disliked the necessity of dispersing these non-violent crowds and although the injuries inflicted on the law-breakers were almost invariably very slight the idea of using force against such men was very different from the more cogent need for using it against violent rioters who were endangering other men's lives. At the same time I realized that the law-breakers could not be allowed to continue their deliberate misbehavior without any action by the police.[20]

Curry's response suggests the power of nonviolent action to create a dilemma among officials charged with responding to it.

The players were the independence movement, led by Gandhi, and the British raj, led by the viceroy, Lord Irwin. Note that particularly significant individual players - Gandhi and Irwin - stand out from, while being part of, the compound players. Gandhi initiated the engagement.

Available arenas included private interactions, courts, media and public spaces. The activists chose to play on the arena of public space, amplified by word-of-mouth and media coverage. However, Gandhi began by writing to Irwin - ostensibly a private interaction - to allow him to respond appropriately and avoid civil disobedience.

Types of dilemmas involved included moral (for example, for the policeman Curry), interpersonal (Gandhi corresponding with Irwin), inter-organizational (the salt march organizers versus the British rulers), political (challenge to British rule) and economic (challenge to the salt monopoly).

The opponent's choices included letting the march proceed and arresting Gandhi. In the longer term, another choice was offering negotiations or concessions.

The consequences of the salt march included arrests and beatings (in the short term) and massive mobilization of support for Indian independence (both short and long term).

How did the salt march dilemma action differ from other possible actions ? One feature that made it powerful was the choice to focus on the salt tax and salt monopoly. In objective terms, this was hardly the more serious issue experienced by the Indian people, given massive economic exploitation, lack of self-determination and occasionally brutal treatment. In the spectrum of oppression, the salt laws were a minor matter - but they symbolized British rule and affected nearly everyone.

Second, the salt march was designed to begin small and gradually build. This meant there was no single point along the way to provide a pretext for arrests or controls. To follow his own laws, the Viceroy had to wait for civil disobedience to occur, at the end of the march.

Third, Gandhi's central role in the march heightened the dilemma. If some other figure, with less stature, had led the march, it would not have attracted the same attention throughout India. Irwin could have ignored the march without Gandhi, treating it as unthreatening, or arrested the leader at an early stage without the opprobrium of arresting Gandhi.

In the early 1980s, conscientious objectors created a number of dilemmas for the Norwegian government. All were what Jasper calls single players, namely individuals who refused conscription based on strong objections against participating in war, individually confronting an apparently almighty compound player.

Most conscientious objectors fitted into the system of the time - they had no trouble explaining their strong pacifist convictions, their objection to participating in any wars and their willingness to undertake substitute civil service. Some men became "situation-dependent objectors" because they did not want to fight in wars under the present system, frequently referring to Norway's membership in NATO and the threat of nuclear war. Other men were "principled total objectors" who also refused civil service, stating that the substitute service was part of the military system and it was against their conscience to support any part of this system. Both types of objectors presented a dilemma for the Norwegian state.

For refusing to obey orders, the situation-dependent objectors were usually convicted twice to three-month prison sentences. During social democratic governments they were usually pardoned the second time, but not during conservative governments. The situation for the total objectors was even harsher: 16 months in prison, a treatment unlike anywhere else in Europe. Officially, it was not considered punishment: the total objectors had to carry out their substitute service in an "institution under the administration of the prison Administration." This contradiction - that what appeared to be a punishment was called something else - became the core of the total objectors' spectacular protests, revolving around their court hearings and prison time and generating newspaper headlines like "Prison is not punishment." Even their court hearings were not real court cases, because their only purpose was to establish their identity. They were not charged with anything criminal, and their service in prison was not entered into the criminal record. Nevertheless, media frequently reported as if this was a serious criminal offence, giving total objectors a right to compensation and showing that the Norwegian state had a difficult time explaining its practice.

During the early 1980s the plight of total objectors and situation-dependent objectors became widely known, largely due to their own efforts to place it on the political agenda. Their visibility also stimulated more men to object. Many objectors and their supporters had experience in other political movements for peace, justice and the environment. The objectors' main compound player was Kampanjen Mot Verneplikt (KMV), which means "Campaign Against Conscription." It was a network of total resisters launched in November 1981 and part of an international campaign for total objection originating in 1974.[21]

Between 1981 and 1989, KMV undertook many spectacular actions. To better accommodate the situation-dependent objectors, it was sometimes done in the name of an even more informal network called "Samvittighetsfanger i Norge" (S.I.N), "Prisoners of Conscience in Norway." One of the objectors, Jørgen Johansen, produced a poster in connection with his court hearing in 1982 where he would be given 16 months in prison. He invited the public to come and watch this "drama in several acts arranged by the court and KMV."[22] In 1984, another young man set fire to his conscription book during his court hearing and said,

This is not a court case. I will be told that I'm going to prison for 16 months, but I could have received that in a letter. Instead they dress this in a legal frame. The only thing the judge is to do is to establish that I'm Harald Eraker and that I refuse substitute service.[23]

When another young man was about to receive his 16-month sentence, Johansen "borrowed" a prosecutor robe and pretended to be the prosecutor in the case: the real prosecutor seldom bothered to show up in these cases where the result was foregone.[24] Johansen also applied to have his case tried before the European Commission of Human Rights in Strasburg, and a hearing was held in October 1985.[25] Although the commission decided that "Johansen vs. Norway" was inadmissible, it was only the second case against the Norwegian state to even be considered for admission and with all likelihood was an embarrassment for the Norwegian state.

On three occasions, KMV and S.I.N created dilemma actions by staging a "jail-in": they jumped the fence and into the prison or sat on the prison wall, demanding to be with their imprisoned friend. The first jail-in took place on midsummer night in June 1983, when situation-dependent objector Johan Råum was in prison. 12 people managed to climb up on the prison wall of Oslo Kretsfengsel with ladders, and 10 of them then jumped into the prison yard. Their demand was that either Johan Råum should be let out of prison, or they should all be locked up together with him since they had the same beliefs.[26] Similar jail-ins were organized in 1984 and 1987.[27] On the day of the jail-in, the prison authorities and then the police faced the dilemma of how to deal with the protestors on the spot, in particular whether to carry them away or let them stay in the prison as they demanded. The prisoners were allowed to hold a press conference together with their friend, and when they left the prison they were arrested and carried away by the police.[28]

Afterwards, a new dilemma arose for the prison authorities and prosecutor: charge them for trespassing or pretend that nothing happened? In spite of a written confession, the case was "dismissed for lack of evidence" - the same thing that happened in the prosecutor case.[29] KMV interpreted this to mean that the authorities did not want any further publicity about the incident. Nevertheless, the long term dilemma remained for the politicians: should the law regarding total resisters be changed or should they hold their ground? KMV could be expected to carry out every imaginable action, had shown ability in inventing new ideas, and kept growing. Although still a tiny proportion of all conscripts, there were more total resisters than ever thanks to their organizing and the publicity they received. Total resistance was on the agenda as never before, being discussed in parliament and debated in major newspapers, with journalists questioning parliamentarians about the issue.[30] The Norwegian state had to defend its practice in front of the commission to decide on "Johansen vs. Norway," an issue it took so seriously that no total objectors were imprisoned while the case was pending . Amnesty International debated whether it should adopt them as prisoners of conscience. Towards the end of the 1980s the law was in fact changed; KMV felt certain that it had had a huge influence.

The KMV's dramatic and provocative actions were effective in gaining attention and attracting support. In comparison, traditional forms of protest such as rallies and letter-writing campaigns, which are common in liberal democracies, would have been very unlikely to have had the same effect, since the total objectors were so few. Without the spectacular action to create attention, hardly anyone would have heard about their fate. Had there been large numbers of total resisters, the burden on the court and prison systems might have pressured the government to change the law. But although the number of total resisters grew, they remained a tiny proportion of the conscientious objectors and were never likely to become a substantial part of the prison population.

KMV's actions were clearly focused on the legal system, which from their perspective appears to be an obvious choice. By choosing prisons and courts as arenas for their action they were proactive, because these institutions are traditionally dominated by the authorities. Many other arenas traditionally used for protest were also available, but using them would have been less spectacular. If KMV had been interested in the arena of words rather than actions, they could have put more focus on the irony of their prison time being a "service to society," but they did not go down this path in their actions. The authorities actually admitted that the reason for the 16-month prison "service" was to uphold respect for military service and convince most citizens to comply with the military and civil service.

The players were individual objectors, KMV and the Norwegian government. KMV initiated the engagements.

Available arenas included courts, prisons, media and public arenas. The activists chose to play in the courts and prisons as a way to generate media coverage.

The main type of dilemma involved was political (challenge to Norwegian government policy). The opponent's choices included ignoring the protesters or legally charging them. In the longer term, another choice was changing the conscription law.

The consequences of the KMV actions included publicity for total resistance and situation-dependent objection (in the short term) and changing the law (long term).

How did the KMV dilemma actions differ from other possible actions ? By using spectacular strategies, the protesters generated more publicity than conventional sorts of protest and complaint, and more sharply highlighted the contradictions in the government's rationale for its policy.

In 2010, a convoy of six ships set out to challenge the blockade of the Gaza strip, posing a dilemma for the Israeli authorities imposing the blockade. On board the ships were around 700 unarmed civilians from around the world, including some well known personalities, like the Swedish crime novelist Henning Mankell and parliamentarians from a number of countries. In addition to the passengers and representatives from the media, the ships also carried 10,000 tons of humanitarian aid, such as building materials and medical equipment like X-ray machines and ultrasound scanners.[31] The long journey meant that the pressure built while the ships approached Gaza, making this a drama for the world to watch.

In this case, there were two major compound players, the state of Israel and the freedom flotilla, each with its own internal struggles about how to handle the situation. However, this case also involved many other players and illustrates how other players can have key roles in a dilemma without being either the initiator of the engagement or the target.

The dilemma the activists created for the representatives of Israel at first sight has two "solutions": either let the ships arrive in Gaza with their passengers and cargo, which in the eyes of many Israeli citizens would mean giving in to pressure. The other option was to stop the vessels, and in that case the next dilemma arose: what means should be used, and when? In the end, commando soldiers from the Israeli Defense Force attacked early in the morning on 31 May, while the ships were still in international waters. On board the Mavi Marmara, nine Turkish citizens were killed, some of them shot dead at close range.[32] The killings created an enormous public relations disaster for the Israeli government, and were condemned around the world. Martin has shown how the use of force backfired on the Israeli government despite its efforts to inhibit public outrage.[33] Many governments summoned the Israeli ambassadors or recalled their own.[34] The relationship with the Turkish government, for decades one of the Israeli government's few allies in the Middle East, was damaged for more than a year. Although the Obama administration in the United States was very restrained in its reactions, it expressed criticism of the Israeli government. A UN commission was established to investigate the attacks, and in August 2011 reached the controversial conclusion that the blockade of Gaza was not illegal, but that the use of force had been excessive and unreasonable.[35]

Stellan Vinthagen, a nonviolent scholar and himself active in the Swedish part of the freedom flotilla, has analyzed the 2010 flotilla as a dilemma action, using Lakey's definition.[36] Vinthagen shows what makes this a dilemma action in contrast to previous actions. On New Year's Eve 2009, 1300 activists from 43 different countries tried to break the blockade by marching into Gaza. This initiative was just as international as the flotilla, but only carried symbolic amounts of humanitarian aid. It was stopped by Israeli authorities. Unlike Vinthagen, we consider this a dilemma action; it was just not as successful as the 2010 flotilla. Since 2008, the Free Gaza Movement had sent several passenger boats to Gaza, some of which arrived successfully. However, they could only carry a small amount of humanitarian aid. Viva Palestina was an initiative that tried to break the blockade by land on three occasions during 2009. However, Vinthagen found that they could not break the blockade since they relied on cooperation with Egyptian authorities, which at that time meant being dependent on the Israeli and US governments.

Vinthagen concluded that two aspects of the 2010 flotilla combined to make this a more powerful dilemma action: (1) it was ordinary humanitarian assistance, not just symbolic amounts, and (2) the delivery by ship meant that the activists were not depending on the Israeli authorities in order to break the blockade. He writes: "A ship is not "on its way" to do an action. The departure itself marks the beginning of the action: the challenge of the blockade. The action had already been going on for several days before Israel had a realistic chance of stopping it."[37] By making the sea the arena instead of the land, Vinthagen thinks the flotilla gained much more control.

Within the freedom flotilla movement there has been discussion about how to make the dilemma even more difficult. The following year, 2011, the campaign planned to repeat the journey, and 12 ships were ready to travel towards Gaza, 10 of them from Greek waters.[38] More ships with passengers from even more countries were chosen as a means for raising the pressure.

However, the Israeli government avoided a repeat of the 2010 scenario by using more subtle ways of stopping the ships. They cultivated relationships with the Greek government, and launched a successful diplomatic offensive which resulted in UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon calling on all governments to urge their citizens not to participate in a second flotilla.[39] The Greek authorities banned the ships from leaving their ports; those that attempted to leave anyway were intercepted by the Greek coast guard.[40] Two of the ships had similar propeller damage, leading to suspicion that they had been sabotaged by the Israeli secret service.[41] The Turkish authorities also prevented the Mavi Mamara from leaving Turkey - in spite of the Turkish government's criticism of the blockade of Gaza. Only one ship, leaving from France, was boarded by Israeli commando soldiers.[42] These events prevented a potential public relations disaster for the Israeli government. The Israeli authorities, by proactive lobbying, dealt with the potential dilemma before it landed on their doorstep. They managed to keep the issue in the arena of permissions to leave ports, thus preventing the activists from reaching their preferred arena, international waters. Bureaucratic obstacles are less newsworthy than a military attack in international waters.

The 2011 attempt to break the blockade is a classic example of how difficult it is to foresee what an opponent facing a dilemma will do when actions and reactions are not routine. The activists had prepared for many different Israeli government reactions, but not foreseen the possibility of bureaucratic obstacles of this kind. One way to surmount such obstacles would have been for the ships to start from different ports in different countries. However, this would have increased the organizational challenge of arriving in Gaza at the same time. It could have been a way of establishing the dilemma over a longer period of time, thereby increasing the pressure; however, it might have been easier to stop them separately using force, without the media drama of the first journey.

The players were the freedom flotilla and the Israeli government. The flotilla organizers initiated the engagements.

Available arenas included the sea, ships, borders and the media. The activists aimed to use ships in international waters as the basis for media coverage.

The main types of dilemma involved were political (challenge to Israeli government policy) and economic (challenge to the blockade of Gaza). The opponent's immediate choices included allowing the ships to deliver their goods and stopping them forcibly. In the longer term, other choices were easing the blockade and preventing the ships from leaving port.

The consequences of the flotilla actions included publicity for the cause of Gaza, publicity about Israeli government's use of force (in the short term) and reducing international support for Israeli policy on Gaza (longer term).

How did the flotilla dilemma actions differ from other possible actions ? Most Israeli use of force, on behalf of its policies on Palestine, is against Palestinians and hidden from international audiences. The flotilla put an international spotlight on Israeli use of force against non-Palestinians undertaking a political-humanitarian action.

Based on our examination of three dilemma actions, plus other instances,[43] the essential feature of such an action is that the opponent has no obvious best response, with the most attractive responses having mixes of advantages and disadvantages that are not directly comparable. In addition we have been able to identify five factors frequently found in actual dilemma actions that add to the difficulty for opponents in making choices: (1) the action has a constructive, positive element; (2) activists use surprise or unpredictability; and (3) opponents' prime choices are in different domains. Dilemma actions can also construct a timing that (4) appeals to mass media coverage, making it difficult for authorities to ignore them. Additionally, as Popovic, Milovojevic & Djinovic suggest, (5) appealing to widely held beliefs can increase the pressure.[44] These factors contribute to making the dilemma more difficult to "solve," but are not essential in constructing it. In both the literature and in the cases we have presented here, it is governments and their agents, such as police and prison officials, that are forced to deal with dilemmas. However, this is not a core feature of a dilemma action, since it can be directed towards private companies, for example banks or other financial institutions.

When we began this study of dilemma actions, we suspected that some of the five factors that can contribute to creating the dilemma would be a necessary part of a dilemma action. Looking at the case studies revealed that they were not. The flotillas had constructive, positive elements but the total resistance campaign did not. The total resistance movement used surprise, but the salt march did not. In the salt march, the opponent's prime choices were in different domains (including moral, interpersonal and political) but in the total resistance campaign they were in the same domain (political). All three case studies involved mass media coverage, but media coverage was less crucial to the salt march dilemma action. The flotillas appealed to widely held beliefs, but the total resistance campaign did not. The three case studies thus illustrate that the five factors can contribute to the acuteness of dilemma actions but are not essential components of them. Activists, when constructing dilemma actions, can consider whether the factors could be useful. Future research might expand this list of additional factors.

Usually the best option for the opponents is to stop the action without anybody noticing. The activists' strategy is then to make it as public as possible. In the freedom flotilla, organizers increased attention by involving people from different countries, including journalists, authors and parliamentarians. The Norwegian total resisters did things so unexpected and newsworthy that the prison authorities felt they could not ignore them.

Many nonviolent actions are reactions to what authorities or multinational companies do: activists respond to agendas set by others. In dilemma actions, activists are proactive, which is one reason why dilemma actions interest activists both theoretically and practically. Although the colonization of India, conscription in Norway, and the blockade of Gaza were the initial starting points for the engagements in the case studies, activists initiated the salt march, the jail-in and the freedom flotilla. They chose the arenas and the timing, forcing authorities to make difficult choices. This also means that for the opponent, preparation becomes more difficult: rather than preparing for a single contingency, for example arresting protesters, authorities might need to prepare for handling fallout from not arresting protesters, if that is the response chosen.

Prior to 1930, salt was just one issue among many in India; it was a routine facet of imperial rule. The salt march created a new agenda, with the arena and timing set by independence campaigners.

Prior to the 1980s, the Norwegian state dealt with total resisters on an individual basis: each individual made the choice in his own home. KMV moved the struggle to public arenas such as courts and prison walls. By the mid 1980s it appeared that the Norwegian total resisters were directing the show, forcing Norwegian authorities to react.

On land, the Israeli government controlled access to Gaza. The freedom flotilla organizers made a conscious choice to make the sea their arena. They could decide when to set out. However, by 2011 they had lost the element of surprise and were unable to foresee the Israeli government's method of responding.

In all three cases, activists framed what they did as something positive and valued. They made salt, went to be with their friend in prison, and delivered humanitarian aid. It became a contest over what was really going on - a framing contest. Authorities could choose to interpret the actions in the same ways as the activists. Alternatively, if they chose not to accept this positive and constructive framing, and insisted on treating the activists as provocateurs and law breakers, they faced the challenge of explaining what was wrong with making salt, supporting a friend who is in prison but not being punished, and sending emergency aid to a disaster area. Popovic, Milovojevic & Djinovic suggested that forcing an authority to go against a widely held belief or give in to activist demands is the essential part of a dilemma action;[45] here we find examples of how the emphasis on widely held positive values helps make the dilemma more difficult. However, we do not consider this an essential feature of a dilemma action.

Regarding the freedom flotilla, Vinthagen (2010) suggests that two key aspects were that by choosing the sea the activists were much more in control and that the amount of humanitarian aid was more than symbolic. These accord respectively with an essential characteristic of dilemma actions, initiating the engagement, and a frequent one, a constructive element. However, the two other cases do not include any equivalent to humanitarian aid: in the case of the Norwegian total resisters, the constructive element of supporting a friend does not appear to be essential for that action. It is possible to imagine other powerful dilemma actions that do not include any such element.

Creating a dilemma for opponents is, naturally enough, a key feature of dilemma actions. Dilemmas can be more difficult when they involve different domains, for example when one choice has ideological consequences and another has political consequences, because these consequences are not readily compared.

Regarding the salt march, Lord Irwin had a choice between arresting someone who had not done anything illegal - which included a moral component - and allowing the march to proceed, with a political impact on Indian and international public opinion.

One thing to take into consideration is different audiences. It is frequently difficult to compare the benefit of an approving reaction from supporters with negative feedback from a different audience. Israeli authorities had to compare their image of themselves as upholding a blockade meant to protect Israel with the outrage generated when international audiences saw this as an assault on humanitarian aid workers in international waters. A special audience is the mass media, which are often crucial in spreading the news of the action to other audiences.

Unpredictability was also a factor hindering the process of comparing choices. Neither the Israelis nor the freedom flotilla could readily predict or control how the Turkish government or people would react and what consequences their reaction would have in the long run.

Timing is another aspect of dilemma actions highlighted by the case studies. A challenging dilemma not only means that the players have to make choices between incomparable realms, but also that there are short, middle and long term consequences to take into consideration. What seems to be a good solution in the short run might backfire in the long run. Additionally we notice that in both the salt march and the freedom flotilla there was a long build up before the climax of the direct confrontation. Everyone involved, including mass media, is aware that something dramatic is going to happen.

All of these characteristics can also be found in other nonviolent actions, which is why we do not want to draw a sharp line between what is a dilemma action and what is not. Earlier we mentioned that ploughshare actions involving damage to weapons are not dilemma actions. Looking at the characteristics we have identified we see that the ploughshare actions often involve surprise regarding when and where. But it is not difficult for the authorities to compare the consequences of arresting versus not arresting the activists, so the essential feature is lacking. However, creating dilemmas for the opponent is not necessary for nonviolent actions to be successful in the eyes of their organizers or bystanders.

Experience in responding to dilemma actions can change the opponent's calculation: as opponents learn more about a particular type of action, they prepare, so the dilemma is different or not present; therefore activists need to change their plans and preparation to ensure that there is a dilemma. The freedom flotilla experience from 2011 reveals how Israeli authorities learned how to defuse a potential repetition of the 2010 experience; this provides additional evidence that the 2010 events backfired on the Israeli government.

So far, we have discussed nonviolent dilemma actions targeted at governments, but dilemma actions are not automatically for a just cause. It is also possible for governments and others with power to undertake dilemma actions, aiming to split movements, defuse protests, mislead public opinion, and discredit protesters. Most commonly these involve violence or the threat of violence.

During the Nazi occupation of Denmark 1940-1945, the occupiers created dilemmas for the resistance movement. When the resistance movement carried out liquidation of informers or acts of sabotage, the Nazis in revenge organized so-called clearing murders: extrajudicial killings of members or suspected members of the resistance, prominent Danes or randomly chosen civilians. The first to be killed this way was the well-known priest and poet Kaj Munk. Another form of "counter-sabotage" was blowing up well-respected businesses or buildings, such as the amusement park Tivoli's concert hall. The situation was not presented as a dilemma officially, since in contrast to other places in occupied Europe, the Nazis in Denmark never admitted being behind the counter-sabotage. Nevertheless, within the resistance movement and the general public, there was no doubt about the dilemma involved: the resistance movement had to compare the effect of sabotage and informer liquidation to the loss of people like Kaj Munk, and the possibility of loss of support from the general population.[46]

A comparable dilemma arose for the members of the organization Peace Brigades International (PBI) in Sri Lanka in 1993. They had been carrying out unarmed accompaniment as protection to local human rights activists threatened by the Sri Lankan government. Both they and those they accompanied felt that their presence provided some protection and made a difference. They also tried to support a group of Tamil refugees living in Colombo about to be relocated by the government to the war-torn Northeast Province against their will and managed to prevent the first group of refugees from being forcefully relocated. But then the Sri Lankan authorities created a dilemma for PBI. Via foreign embassies, they let it be known that if PBI insisted on involving itself in the refugee issue, the organization would lose its permission to work in the country. PBI was then faced with the dilemma of withdrawing from this particular case (which it did) in order to be able to continue other parts of its work.[47]

Finally, there are some rare instances in which authorities have used nonviolent methods against peaceful protesters. In 1930 during the Indian independence struggle:

... a huge procession of Satyagrahis was stopped by armed police on one of Bombay's main streets. About 30.000 men, women and children sat down wherever they were on the street. Facing them sat the police. Hours passed but neither party would give in. Soon it was night and it began to rain. The onlooking citizens organised themselves into volunteer units to supply the Satyagrahis with food, water and blankets. The Satyagrahis, instead of keeping the supplies for themselves, passed them on to the obstructing policemen as a token of their good will. Finally the police gave in, and the procession culminated in a triumphant midnight march.[48]

For the Satyagrahis, stepping on the police to reach their goal was not a viable option, so instead they sat down and waited as well: there was no real dilemma for those committed to nonviolence. When the police were treated with respect and kindness, it was they who faced a dilemma, namely whether or not to continue to block the Satyagrahis.

Dilemma actions are a type of action in which opponents have to make a choice between two or more responses, each of which has significant negative aspects; the responses are not readily comparable, which is the nub of the dilemma. Dilemma actions can be characterized by the players involved, the initiator of the engagement, the arena chosen for the action, the domain of the dilemma, the choices made and the location of the action within the "option space" of possible actions.

Dilemma actions are not easy to analyze in depth using game theory or other sorts of strategic frameworks, because usually compound players are involved, whose members differ in their judgments about the attractiveness of options. Furthermore, players can change the payoffs from different options by investigating new possibilities, making preparations or playing unexpected moves. As a result, the same game is seldom played repeatedly without change. The changes in the freedom flotilla scenarios between 2010 and 2011 are a case in point.

For activists, dilemma actions can seem attractive because they seem to offer the prospect of success no matter what the opponent does. In a typical dilemma action involving nonviolent action, the opponent can either let the activists proceed to achieve their immediate goals or use force to stop them with the risk of adverse publicity. However, on the surface there seems no obvious reason why dilemma actions are superior to actions in which the opponent has a single best option.

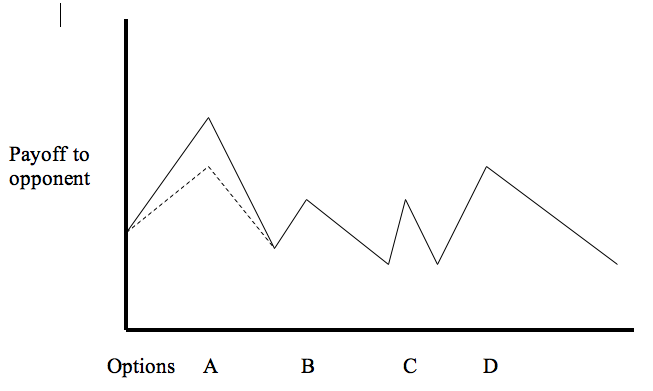

One way to see the advantage of planning dilemmas is illustrated in Figure 1. Of four main options, A through D, A is clearly superior for the opponent. Preparation by activists - for example, by arranging publicity so that the opponent's use of force will be more counterproductive - changes the payoff for A so that it is similar to the payoff for D: the opponent's previous best option is no longer clearly superior. Figure 1 presents options as different in one dimension, with a clear-cut payoff for each that can be compared; in reality, options and payoffs may vary across several dimensions, including diverse domains, and payoffs may be uncertain and non-comparable. The creation of a dilemma action can be considered a process of designing an action in which the normal or default response by the opponent is made less attractive than it might otherwise be. Planning to put the opponent in a dilemma can be a way of stimulating thinking about how to reduce the attractiveness of the opponent's regular or most attractive response.

Figure 1 Opponent payoffs for four options, A through D. Following activist preparations to reduce the attractiveness of option A (dotted line), the opponent faces a dilemma in choosing between A and D.

Starting with the limited amount of writing about dilemma actions, we have extracted the essential characteristic of such actions, presented a range of domains in which dilemmas can be posed, and shown the value of a series of questions for analyzing actual dilemma actions. Much remains to be studied concerning dilemma actions. Investigating more case studies, including ones involving different domains, could enable assessment and refinement of our essential features and typical but non-essential features. This should also include comparisons with cases of nonviolent action that do not include a dilemma. The use of dilemma actions by authorities against activists would also be a fruitful area for study in order to understand both nonviolent and violent dilemmas better. Yet another area worth investigation is the possibility of creative responses to dilemma actions, including counter-dilemmas.

More generally, the study of dilemma actions means looking at tactics on both sides of strategic encounters involving activists and authorities. Nonviolent action theory in the tradition of Sharp (1973) has focused on what activists do and seldom looks at a full range of actions by authorities. Examining dilemma actions thus provides a way of expanding nonviolent action theory.

We thank Jørgen Johansen, George Lakey, Stellan Vinthagen, Tom Weber, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on drafts.

1. George Lakey, Powerful Peacemaking: A Strategy for a Living Revolution (Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1987 [1973]).

2. Srdja Popovic, Andrej Milovojevic, and Slobodan Djinovic, Nonviolent Struggle: 50 Crucial Points, 2d ed. (Belgrade: Center for Applied Non Violent Action and Strategies, 2007), 70-71.

3. Ibid. , 71 .

4. Bill Moyer, with JoAnn McAllister, Mary Lou Finley, and Steven Soifer, Doing Democracy: The MAP Model for Organizing Social Movements (Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers, 2001).

5. Philippe Duhamel, The Dilemma Demonstration: Using Nonviolent Civil Disobedience to Put the Government between a Rock and a Hard Place (Minneapolis, MN: Center for Victims of Torture, 2004), 6.

6. Richard B. Gregg, The Power of Nonviolence , 2d rev. ed. (New York: Schocken Books, 1966 [1934]).

7. Thomas Weber, "'The Marchers Simply Walked Forward until Struck Down': Nonviolent Suffering and Conversion," Peace & Change, Vol. 18, No. 3 (1993): 267-289.

8. Gene Sharp, The Politics of Nonviolent Action (Boston: Porter Sargent Publisher, 1973).

9. Brian Martin, Justice Ignited: The Dynamics of Backfire (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield , 2007).

10. Christopher W. Gowans, Moral Dilemmas (New York: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987); H. E. Mason, Moral Dilemmas and Moral Theory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Terrance McConnell, "Moral Dilemmas," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-dilemmas/.

11. William Styron, Sophie's Choice (London: Vintage, 2000, 1979).

12. James M. Jasper, Getting Your Way: Strategic Dilemmas in the Real World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

13. Ibid., 83.

14. Ibid., 92.

15. Thomas Weber, On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi's March to Dandi (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 1997).

16. Dennis Dalton, Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 112.

17. Bipan Chandra, India's Struggle for Independence, 1857-1947 (New Delhi: Viking, 1988), 273-274.

18. Young India, 29 May 1930, quoted in Weber, "'The Marchers Simply Walked Forward until Struck Down,'" 281.

19. Dalton, Mahatma Gandhi, 130.

20. Ibid., 133.

21 ICR Skandinavia, Verneplikt: Statlig Tvangsarbeid: Et Hefte Fra ICR-Skandinavia [Conscription: State Forced Labour: A Booklet from ICR-Scandinavia], (Bergin: Fmks Fredspolitiske Skriftserie, 1981), 4.

22. HA, "Totalnekter [Total Objector]," Halden Arbeiderblad (April 21, 1982).

23. Kirsten Offerdal, "Brann Vernepliktsboka Si I Rettssalen [Burned His Conscription Book in Court]," Vårt Land (May 11, 1984).

24. Jørgen Johansen, "Humor as a Political Force, or How to Open the Eyes of Ordinary People in Social Democratic Countries," Philosophy and Social Action, Vol. 17, No. 3-4 (1991): 23-29.

25. Kjell Eriksson, "Klagen Avvist I Strassbourg [The Complaint Dismissed in Strasbourg]," Sarpsborg Arbeiderblad , October 15 1985.

26. Gunnar Fortun, "Rømning - Feil Vei," Arbeiderbladet (June 24, 1983); Johansen, "Humor as a Political Force."

27. Aftenposten, "Aksjon På Fengselsmurer," Aftenposten (May 4, 1987); Stig Grimelid, "Ex-Fange Tilbake," VG (August 28, 1984); Esther Nordland, "Inntok Fengselsmurene," Arbeiderbladet (August 28, 1984).

28. Johansen, "Humor as a Political Force."

29. Ibid.; Åsne Berre Persen and Jørgen Johansen, Den Nødvendige Ulydigheten [The Necessary Civil Disobedience] ([Oslo]: Fmk, 1998).

30. KMV, "Rundbrev 9," Kampanjen Mot Verneplikt (November 1984).

31. Moustafa edt Bayoumi, Midnight on the Mavi Marmara: The Attack on the Gaza Freedom Flotilla and How It Changed the Course of the Israel/Palestine Conflict (New York: OR Books, 2010).

32. Paul McGeough, "Prayers, Tear Gas and Terror," Sydney Morning Herald (June 4, 2010).

33. Brian Martin, "Flotilla Tactics: How an Israeli Attack Backfired," Truth-out.org (July 27, 2010).

34. Bayoumi, Midnight on the Mavi Marmara.

35. BBC, "Gaza Ship Raid Excessive but Blockade Legal, Says UN," BBC News (September 2, 2011); Geoffrey Palmer et al., Report of the Secretary-General's Panel of Inquiry on the 31 May 2010 Flotilla Incident (United Nations, 2011).

36. Stellan Vinthagen, "En Ny Sorts Dilemma-Aktion [A New Kind of Dilemma Action]," in Ship to Gaza: Bakgrunden, Resan, Framtiden [Ship to Gaza: The Background, the Journey, the Future], ed. Mikael Löfgren (Stockholm: Leopard, 2010).

37. Ibid., 186.

38. Jack Shenker and Conal Urquhart, "Activists' Plan to Break Gaza Blockade with Aid Flotilla Is Sunk," The Guardian (July 5, 2011).

39. Ann Wright, "The Israelis Mount a Diplomatic Offensive to Stop the Gaza Flotilla," Truth-out.org (April 16, 2011); Joshua Mitnick, "Israel's New Friend: Why Greece Is Thwarting Gaza Flotilla," Christian Science Monitor (July 5, 2011); Reuters, "UN Chief: Discourage New Gaza Flotilla," ynetnews.com (May 27, 2011).

40. Postmedia, "Activist Flotilla Stopped in Greece," Canada.com (July 1, 2011).

41. Richard Falk, "Sabotaging Freedom Flotilla II," Aljazeera.com (July 2, 2011).

42. BBC, "Israel Troops Board Gaza Protest Boat Dignite-Al Karama," BBC (July 19, 2011).

43. Duhamel, Dilemma Demonstration; Lakey, Powerful Peacemaking; Popovic et al., Nonviolent Struggle; Sharp, Politics of Nonviolent Action.

44. Popovic et al., Nonviolent Struggle .

45. Ibid.

46. Claus Bundgård Christensen, Danmark Besat: Krig Og Hverdag 1940-45 [Denmark Occupied : War and Everyday Life 1940-45], 3. reviderede udgave (Ny revideret udgave), 1. oplag. ed. (Kbh.: Information, 2009), 539-552.

47. Patrick G. Coy, "Shared Risks and Research Dilemmas on a Peace Brigades International Team in Sri Lanka," Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 30, No. 5 (2001): 594-599.

48. Krishnalal Shridharani, War without Violence: A Study of Gandhi's Method and its Accomplishments (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1939), 21-22.