In Australia as in many other countries, there grew up in the latter half of the 1970s a major citizens movement against nuclear power. The Australian struggle against nuclear power has mainly been a struggle against uranium mining in Australia's Northern Territory. Here I give a general account of this struggle, covering the origins of the Australian anti-nuclear movement, issues in the nuclear debate and the strategy of the movement. But to begin, a bit of background on the Australian situation may be useful.

The Australian political system is a formal liberal democracy based in a capitalistic economic system. The major sectors of the economy are dominated by large corporations, many from Britain, U.S. and Japan. Government intervention in the economy is significant but relatively low by European standards. Provision of social services is fairly unsystematic. The Liberal-Country Party has been in government since 1949 except for the period 1973-1975; it is closely linked to business interests. The other major political party, the Australian Labor Party (ALP), although nominally socialist, is for the most part committed to managing capitalism better and providing better social services. The union movement is relatively strong, contains some socially conscious sections, and is closely linked with the ALP.

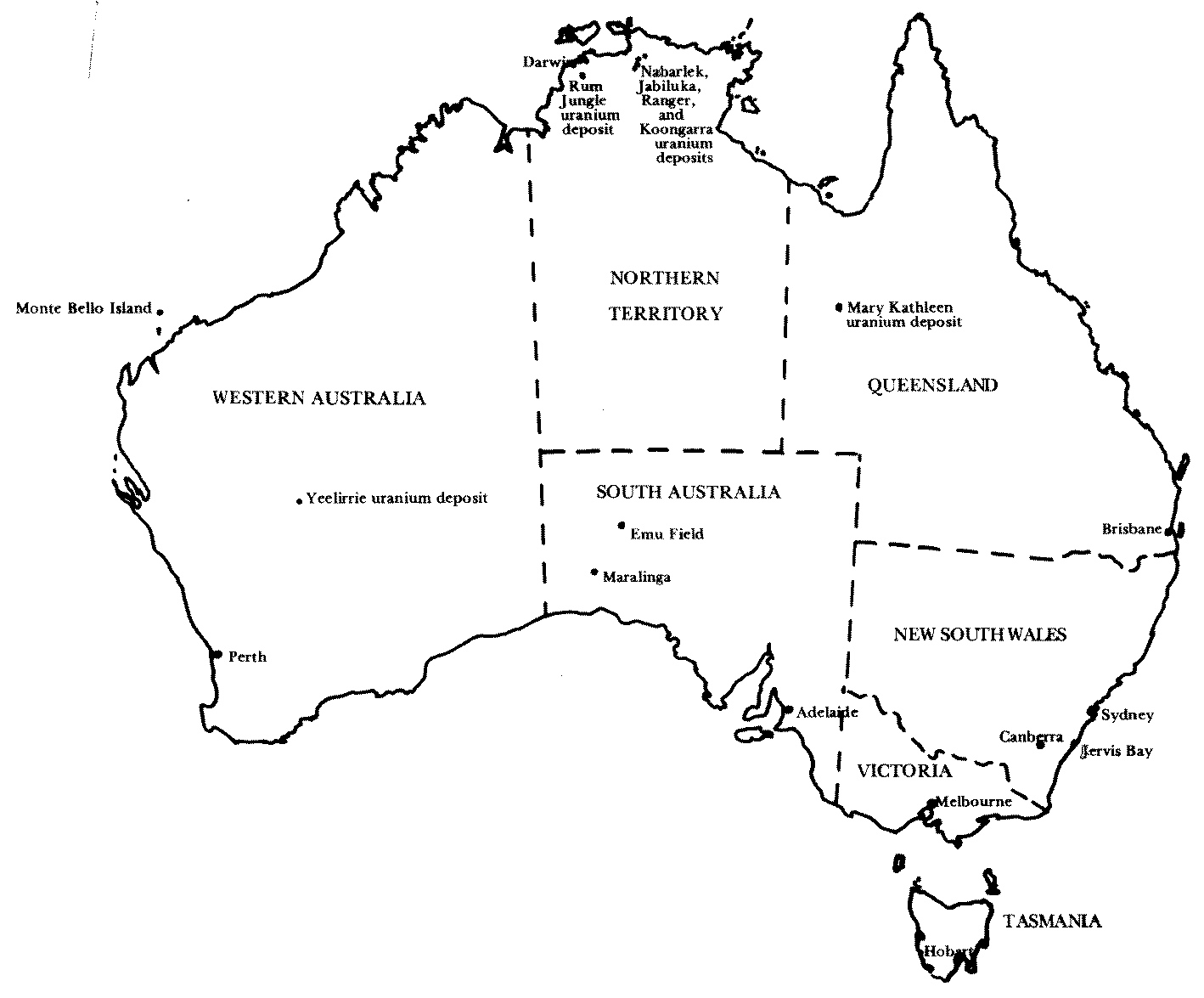

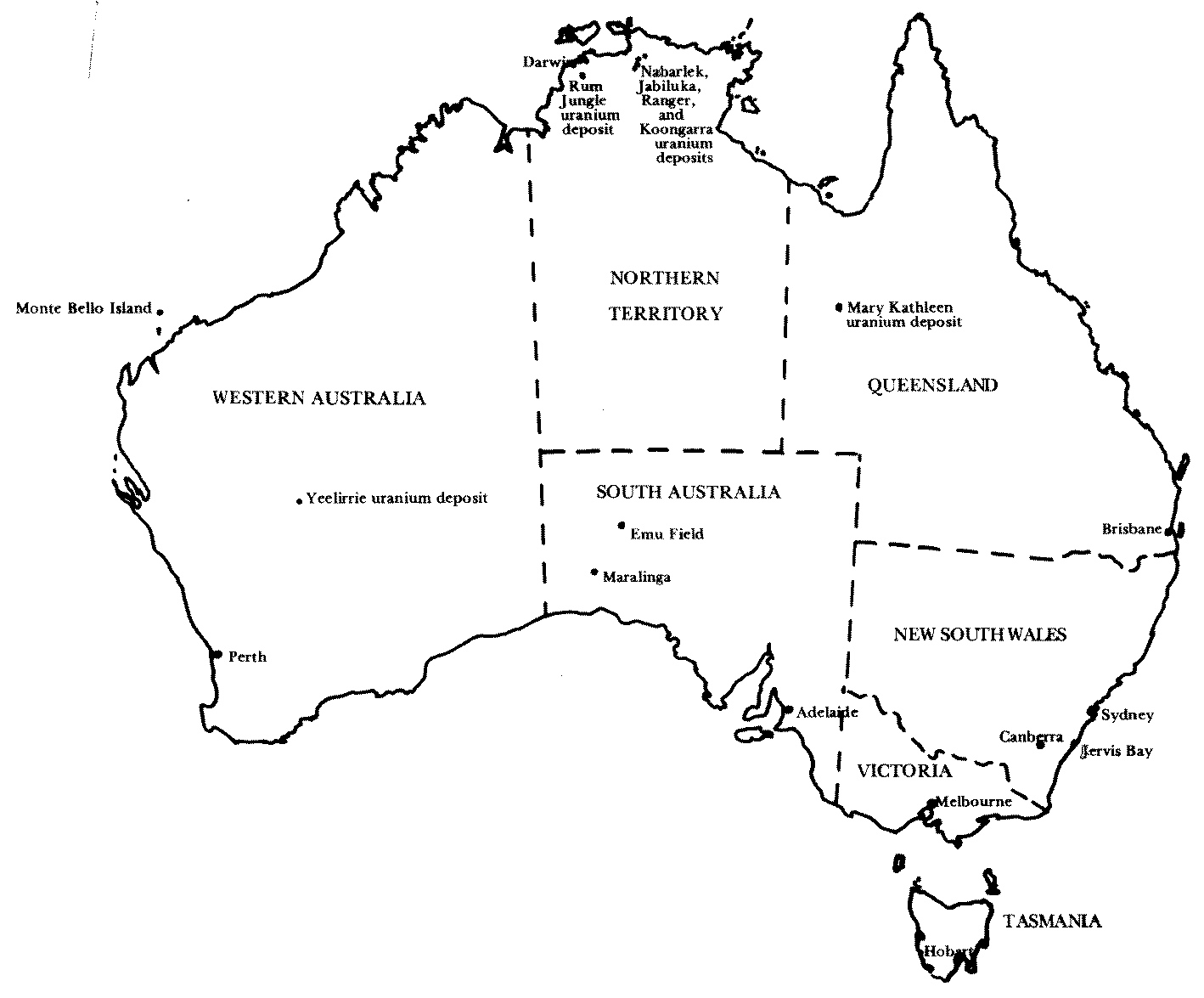

Australia's first experiences with nuclear matters grew out of the production of nuclear weapons during and after World War II. Several uranium mines in Australia were used to produce uranium for the British nuclear weapons programme. In the 1950s, 12 British nuclear weapons were tested in Australia, at Monte Bello Island off the northwest coast and at Emu Field and Maralinga in South Australia. In 1953 the Australian Atomic Energy Commission (AAEC) was set up to undertake and promote nuclear research and oversee mining of Australian uranium. The most significant mine was at Rum Jungle in the Northern Territory which operated from 1958 until about 1970.

Because of its abundant supplies of low cost coal, nuclear power has never been an economic proposition in Australia. However, under the influence of the AAEC and especially its Chairman Sir Philip Baxter, the federal government in 1969 announced plans for a nuclear power reactor at Jervis Bay. But with a new Prime Minister after a Liberal Party leadership struggle, the plans were abandoned mainly for economic reasons. About the same time, a bureaucratic battle was carried on over the Treaty for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The Liberal-Country Party government delayed signing for two years, revealing the influence of pressures for keeping open the option for Australian nuclear weapons. The NPT was not ratified by Australia until after the election of the Labor government in late 1972.

The first major public debate relating to nuclear matters was in 1972 and 1973 over the atmospheric testing of French nuclear weapons in the Pacific. The Labor government took the French to the International Court of Justice over the matter in 1973. The pressures in Australia and throughout the Pacific region led the French to move their testing programme underground and to discontinue publicising explosions.

In the 1960s, due to the drop in demand for uranium for Western nuclear weapons programmes and the consequent drop in price, Australian uranium mines successively shut down. But in the early 1970s several rich uranium deposits were discovered, especially in the Northern Territory. Together with the increasing price of uranium reflecting the planned growth of nuclear power, this increased the pressure to begin large scale uranium mining in Australia. Reflecting the change in the price of uranium, the small Mary Kathleen mine, closed in 1969, was re-opened in 1975. But the primary focus of attention was on the Northern Territory deposits, especially the large ones at Jabiluka and Ranger.

The Australian uranium reserves are significant both physically and politically. The Australian high-grade reserves constitute about 15 to 20 percent of world high-grade reserves, while Australian reserves of lower grade uranium are a smaller proportion of world lower grade uranium. The high grade and easy accessibility (open, not closed pit mining) of Australian uranium means that it is potentially profitable for companies to mine and sell it even if there are sufficient supplies internationally to meet demand. The main impact of Australian uranium in the latter situation would be to lower the international price of uranium (assuming no cartel), to lower profits on Australian uranium and to make some non-Australian operations marginal.

Australian uranium is even more potentially significant than the figure of 20 percent of world high-grade reserves would suggest. The other countries with known large uranium reserves are the USSR, USA, Canada and South Africa (including Namibia). Governments of present and future uranium importers, such as Japan and EEC countries, prefer reliable and secure supplies. The USSR does not export its uranium. Uranium supply from South Africa could be disrupted easily as a result of political upheaval. And most US and some Canadian uranium production is used directly in the large US nuclear programme. Hence Australian uranium is a very significant fraction of uncommitted, low-cost uranium on the world market.

In 1974 in Australia, the general advisability of uranium mining was almost uniformly unquestioned in business and industry, government bureaucracies, political parties, labour unions and the general public. Indeed, who had ever heard of leaving a mineral in the ground which could be mined with a minimal amount of trouble and effort and sold for a lucrative profit?

However, several factors led the Labor government to delay a rush into mining: a concern over Aboriginal land rights (since one of the last preserves of traditional Aboriginal life styles was in the region of the major uranium deposits), a willingness to wait for yet higher uranium prices, the existence of the recently passed environmental protection laws, and pressure from some sections of the public and the Australian Labor Party itself which were concerned about the hazards of uranium mining and nuclear power. The government set up a wide ranging inquiry into uranium mining at the Ranger deposit in the Northern Territory in July 1975. In November 1975 the Liberal-Country Party suddenly took over the government in a manner of dubious constitutionality; an election shortly afterwards went strongly in their favour.

The new government was fully committed to uranium mining, but waited before formally announcing its decision for the reports of the Commission conducting the inquiry, which were made in October 1976 and May 1977. In August 1977 the go-ahead for mining was given, but under condition that permission be obtained first from the traditional Aboriginal landowners. Due to various delays, particularly in manipulating an agreement with the Northern Territory Aboriginals, mining operations did not begin at any sites until the first part of 1979. Starting in 1981 some uranium from the small Nabarlek mine has been exported.

The Australian anti-nuclear movement had several roots. The 1972-73 debate over French nuclear testing had mobilised several groups, including a number of trade unions such as the Seamen's Union and the Plumbers and Gasfitters Union. Representing union concern, Bob Hawke, president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, spoke against the French tests at the International Labor Organization. Some unions, such as the Waterside Workers Federation, took direct action with black bans.

After the public debate over French tests subsided, some of the unions maintained a concern over nuclear issues. In 1974 and 1975 this concern came to focus on uranium mining in Australia. For example, there was strong union involvement in the first major anti-uranium broadsheet, entitled "A slow burn", published by Friends of the Earth in September 1974. In 1976 there was a one day national strike over uranium by the Australian Railways Union, one of the earliest such major anti-uranium actions.

Secondly, grass-roots activist organisations in the major Australian cities began focussing on nuclear power and uranium mining in 1974 and 1975. Most notable were the recently formed Friends of the Earth groups, some of which grew out of Greenpeace groups which had opposed French nuclear testing. In most cases a few key individuals were primarily responsible for getting the organisations going or focussing on uranium mining. But of course a few individuals cannot stimulate the growth of a major movement unless a chord of popular concern is struck through the issues debated, the ideas presented and the demands made.

Thirdly, a number of other organisations began voicing concern about uranium mining and supporting the activities of the grass-roots organisations. Important organisations in this respect were the national environmental body the Australian Conservation Foundation, the small but vocal political party the Australia Party, and a number of university student organisations.

Finally, the Australian anti-nuclear movement also acquired initial impetus from various individuals who privately and, more importantly, publicly voiced concern about the nuclear option. Examples are nuclear scientists Richard Temple and Rob Robotham and poets Dorothy Green and Judith Wright.

After the small but rapidly progressing beginnings in 1974 and 1975, the years 1976 and 1977 saw the uranium issue become a major political issue. This occurred because of the deliberations and reports of the Ranger Inquiry, the lack of any announced decision by the government, and the efforts of the opponents of uranium mining. In addition, many groups demanded that there be a public debate about uranium mining, and many groups - such as churches, unions, ALP branches, local government councils and professional groups - had their own internal debates.

With the broadening of the base of community support for the anti-uranium cause, 1976 and 1977 saw the setting up of local organisations, variously named Movement Against Uranium Mining and Campaign Against Nuclear Energy (or Power), specifically to focus on nuclear and uranium issues. In mid 1977 both the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian Council of Trade Unions adopted stances expressing opposition to uranium mining. The ALP policy was the consequence of much grass-roots effort at the local branch level, something that is quite unusual for the ALP. The period of widespread public debate continued after the government's announcement of uranium mining in August 1977, especially throughout 1978.

[Note: This section is taken from Brian Martin, Nuclear Knights.]

The case against nuclear power and uranium mining in Australia has been concerned mainly with environmental, political, economic, social and cultural impacts of nuclear power, with shortcomings of nuclear power as an energy source and with presenting an alternative energy strategy.

The environmental hazards of greatest concern are reactor accidents, releases of radioactivity in various stages of the nuclear fuel cycle and radioactive waste. Reactor accidents have not received nearly as much attention in Australia as elsewhere, no doubt because Australia has had no realised plans for nuclear power reactors. Significant attention has been focussed on releases of radioactivity in the fuel cycle, particularly during uranium mining, on the hazard of plutonium and on the possibility that low-level ionising radiation is more harmful than officially recognised. Also of great concern has been the problem of long-lived radioactive waste. The Ranger Inquiry's statement that "There is at present no generally accepted means by which high level waste can be permanently isolated from the environment and remain safe for very long periods" has epitomised the basis for concern on the waste issue.

The foremost political impact of nuclear power is its potential contribution towards proliferation of nuclear weapons. The Ranger Inquiry stated unequivocally "The nuclear power industry is unintentionally contributing to an increased risk of nuclear war. This is the most serious hazard associated with the industry". Because of Australia's role as a potential uranium exporter and not a user of nuclear power, the proliferation issue has received great attention, comparatively much more than in most other countries. Other political impacts often raised are the possibility of terrorist or criminal use of nuclear materials.

Due to the potential environmental hazards, proliferation potential and possibilities for terrorist and criminal use, nuclear power poses a threat to civil liberties. Concern over this has been especially significant in Australia since the government gave the go-ahead for uranium mining under a body of highly restrictive legislation, notably the Atomic Energy Act, which was originally used for acquisition of uranium for the British nuclear weapons programme. These laws for example include the possibility of stiff fines and gaol sentences for even speaking out against uranium mining. These powers have not been used but are considered ominous.

Concerning economics, an issue has been made of the large and rising economic costs of nuclear power and of various subsidies which have been made to it such as exemption from full insurance for nuclear accidents. Opponents have argued that the expected returns and export income from uranium mining, while large from the viewpoint of the mining companies, are small on a national scale. Opponents have also argued that uranium mining export income is not likely to be as large as predicted by the companies, that returns are unstable in the light of slowdowns in the worldwide nuclear industry, that much of the profits will go overseas and that many more jobs would be created through alternative investments.

In terms of social impacts, it has been argued that nuclear power would lead to less security for people due to its environmental dangers, increased proliferation potential and scope for terrorist and criminal activities. Also, because of the enormous investments in nuclear power and the need for large organisations and experts to guard against these possibilities, it has been argued that nuclear power leads to a centralisation of political and economic power. Powerful corporations, government bureaucracies and professional groups with a stake in nuclear power, it has been argued, would oppose any move away from nuclear power and hence reduce the scope for democratic involvement in decision-making about energy futures.

Another vital concern has been the detrimental cultural impact which uranium mining, particularly in Australia's Northern Territory, would have on local Aboriginal communities. This impact is due to the violation of sacred sites and of the land itself and due to the destructive impact of the influx of whites and white culture on Aboriginal culture, especially through sexual exploitation, alcoholism and the breakdown of traditional relationships.

Turning to the question of how energy needs are to be satisfied, it has often been pointed out that nuclear power at present provides only about 2 percent of world primary energy and so is not yet an essential source. Furthermore, it is argued that nuclear power cannot contribute much to the real energy 'crisis', an impending shortage of low cost liquid fuel mainly for motor transport, because nuclear power provides only electricity. Even the feasibility that massive nuclear power programmes could cater for ever-growing energy use has been questioned, on the basis of shortages of capital for building nuclear facilities, the long delay between planning and completing nuclear power plants and the slow rate at which plutonium is produced in fast reactors.

The nuclear opponents' own proposals for a non-nuclear energy strategy have mainly followed the case presented by Amory Lovins, in which conservation and prudent use of fossil fuels satisfy energy needs while a transition is made to greater use of renewable energy sources in a highly energy-efficient society. Attention has also been focussed on life style changes and institutional changes such as better public transport, improved facilities for cyclists, and town planning to reduce transport needs.

Special attention has been drawn to the situation of the poor countries of the world. It has been argued that nuclear power is completely unsuitable there because of the shortage of capital and skilled labour, the lack of an electrical infrastructure and the gross inequalities between rich urban elites and the rest of the population. It has been argued that primary emphasis should be placed on local energy technologies such as biogas generators, wind-powered water pumps and more efficient stoves.

Of course opponents of uranium mining and nuclear power differ greatly in the emphases they place on the different arguments and issues. Summarising nevertheless, the case of the opposition can be classified into seven major themes:

While much of the opposition in Australia began and remains centred around environmental hazards, the other themes have attracted an increasing amount of attention and concern.

The major pro-uranium forces in Australia have been the uranium mining companies, major sections of the Liberal-National Country Party government, the Australian Atomic Energy Commission, some government bodies (such as state electricity authorities), portions of the mass media, and a few vocal individual advocates. The Australian business community as a whole has not been conspicuously pro-nuclear or pro-uranium. Even many companies involved in minerals and energy can look to much larger profits from Australian coal, natural gas (off the northwest coast) and aluminium. The uranium companies have had the most to gain, and have made the greatest efforts to promote uranium mining.

In 1976 and especially 1977, a major pro-uranium public advertising campaign was undertaken by the Australian Uranium Producers' Forum, a group set up by the major uranium companies. Also, pro-uranium speaking and letter-writing efforts were organised, especially by John Grover who was paid to do this expressly by the mining companies. This was during the period of so-called 'public debate', before the government's announcement of a go-ahead for uranium mining in August 1977. These publicity efforts produced only mixed benefits for the uranium interests. Since about 1978, pro-uranium forces have kept a much lower profile and may be said to have adopted a strategy of silence. For the example, the Uranium Producers' Forum was disbanded, and replaced by a much lower-key effort. This 'strategy of silence' has posed problems for the anti-uranium movement, especially since participation in anti-uranium groups to some extent depends on the visibility of the uranium issue. It is therefore somewhat ironic that recent proposals for nuclear power plants in Western Australia and Victoria are rekindling concern and action about uranium mining as well.

There is significant foreign participation in many though not all the Australian uranium projects. But the main foreign impact on decisions about Australian uranium seems to operate through the general political and economic pressures to ensure that Australian mineral and energy resources are available to foreign buyers. Since the Liberal-National Country Party government offers virtually unmatched concessions to such buyers, such international pressures as exist would oppose the election of a Labor Party government. Even so, an ALP government would probably only try to strike better bargains with foreign buyers of Australian resources, and would be unlikely to take 'drastic' steps such as nationalising the oil industry.

Indeed, it is really only in the uranium area that ALP policy is greatly at odds with significant international interests. Even so, the international pressures on Australia to mine and sell uranium have slackened, as alternative sources of supply have been developed and as the expected demand for uranium has dropped due to cutbacks in nuclear power programmes worldwide.

Both major political parties claim to adopt policies that look after Australian national interests, and hence no one would use an argument for mining that "we can't fight foreign pressure" - even as they might be giving in to such pressure. The government has used two principal arguments to justify its go-ahead for uranium mining: that the energy-hungry world needs Australian uranium, and that strict export conditions on Australian uranium will help to slow proliferation of nuclear weapons.

These arguments are fairly transparent moral facades for the real reason for uranium mining, namely profit and vested interests. The anti-uranium movement has made the following points in response to the government's posturings. First, the government's rush to promote the mining and export of uranium - a rush explicitly stated to be due to the declining market opportunities for selling uranium - means that there is no crying 'need' for Australian uranium. And due to decreasing demand and increasing supply of uranium, Australian uranium would only reach the world market in a period of uranium glut, when it is least needed.

The government does not distinguish between rich and poor countries when it talks about the world's 'need' for uranium. In fact, the bulk of Australian uranium exports would be to rich countries (Japan, EEC countries), who are not the countries in greatest 'need'. Furthermore, the argument that Australia's low-cost uranium should be exported to rich countries so as to indirectly help the poor countries flies in the face of the lack of other government actions. The government has not lobbied OPEC to sell oil more cheaply to poor countries. There have been no vast expansions of Australian aid programmes to help poor countries with appropriate energy technologies. And there have been no significant efforts to cut back on Australia's profligate use of resources.

In response to the argument that exporting Australian uranium will help slow proliferation, there have been several points made. First, such a stance is entirely incompatible with the government's rush towards uranium mining. Second, the Carter policy for slowing proliferation, which was cited as the rationale for the Australian export safeguards, has been almost a total failure from the beginning. Finally, the best way to stop the introduction of reprocessing plants and fast reactors, which are the prime means for proliferation, is to stop the expansion of the nuclear industry and to promote the adoption of energy conservation and renewable energy sources. Australian uranium would promote an increased dependence on nuclear electricity, would expand the political and economic power of the nuclear establishment and help increase the number of thermal reactors which, upon the exhaustion of uranium reserves, would 'need' to be fueled by plutonium.

The pro-uranium forces have come out much the worse in most public debates so far as presenting convincing arguments is concerned. But as all participants must realise, it is not cogent arguments that decide uranium policy but organised political power. Arguments can help the anti-uranium movement but are clearly insufficient in themselves.

The formulation of an Australia-wide strategy against uranium mining has taken place through an interaction between local groups and national meetings. Local groups are essentially free to plan their campaigns as they wish, but most see coordination as valuable. National meetings of Friends of the Earth and later also Uranium Moratorium (incorporating groups such as Movement Against Uranium Mining) have been held up to 2 to 3 times per year. At these meetings, representatives from local groups discuss general priorities and make decisions. Local group suggestions and opinions are solicited before such meetings and the conclusions discussed locally afterwards. Although decisions of national meetings are not binding on local groups, most groups have followed the general emphases decided upon.

The major campaigns developed have been:

(a) Informational and conscious-changing efforts aimed at particular groups and at the general public, including:

(b) Influencing the ALP and trade unions, mainly through direct contact and through informational efforts such as the above.

(c) Public protests, including national demonstrations (namely, locally organised demonstrations held in different centres on about the same date), pickets at wharves where uranium is loaded for export*, and boycotts.

[* A few export contracts were signed quickly by the Liberal-Country Party government in 1972 just before the federal election which it lost. The small quantities supplied have come from the small Mary Kathleen mine and from Australian Atomic Energy Commission stockpiles. Although the major debate has been over the large Northern Territory mines and over new export contracts for their uranium, the shipments for the earlier contracts have provided a focus for protest by anti-uranium campaigners at the points of loading.]

One problem in executing national strategy has been the division of and taking of responsibility. For example, in the planned boycott of the ANZ Bank (which has strong links with the uranium industry), one group took responsibility for research and basic leaflet production. The actual organisation of the boycott was to be handled locally. But the boycott was never launched due to excessive delays by the one key group. Large distances between Australian population centres partially explain a lack of national coordination, but intergroup liaison has also suffered from a lack of individuals in each area to be responsible for it.

The anti-uranium movement has focussed on four groups in its efforts: (1) trade unions; (2) the ALP; (3) groups and organisations such as churches, schools, doctors and government employees; and (4) the general public. The first two groups provide avenues for directly stopping uranium mining. Key trade unions, if firmly committed and strongly supported by the community, could help to stop uranium mining and export by imposition of black bans. The ALP, if firmly committed and elected to government, could stop uranium mining and export using government powers or passing new laws. Due to their relative lack of direct vested interests in mining, both the unions and the ALP were at least open to argument, compared to the Liberal-Country Party and the mining companies.

In approaching unions and the ALP, every effort has been made to take the issues to workers on the shop floor level and to Labor Party members, though communication at higher levels has not been neglected. The approach of us (anti-uranium activists) versus them (workers) has been avoided. From the beginning, many of the key anti-uranium individuals and groups have been within the labour movement. There has been a mutual interaction between the sections of the anti-uranium movement inside and outside the labour movement. On the one hand, in communication and organising efforts within the labour movement - such as building support for an Australian Council of Trade Unions policy against uranium - many community group activists have contributed by researching the issues, formulating arguments, producing written material, giving talks, lobbying, and generally aiding activists within the labour movement. On the other hand, anti-uranium initiatives from within the labour movement, such as black bans, have been formulated as part of the overall anti-uranium strategy. The interaction has not always been easy or automatic, but has functioned reasonably well. The main obstacle has been as expected: pro-uranium efforts from some parts of the labour movement, especially the more conservative officials.

But the major focus for most anti-uranium campaigning has been the general public. First, the anti-uranium campaign has been based consciously on the assumption that, once aware of the issues involved, a majority of the public would oppose uranium mining. This is not to assume that knowledge and logic by themselves are sufficient as a case against uranium mining (or for it), but that the values associated with the case against are more widespread in the public than those associated with the case for.

Second, trade union or ALP opposition to uranium mining would be unlikely to be sustained without widespread support from the public. Militant action by trade unions on behalf of social issues usually generates considerable opposition from business, government and the media. Public opinion is one major way of opposing these pressures. The ALP is directly influenced by public opinion through the voting process.

Although some efforts have been aimed at 'the public' as an undifferentiated mass, as in the cases of letters to newspapers or street theatre, many efforts have been channelled through existing organisations such as churches, schools and professional groups. Indeed, the emphases on unions and the ALP can be seen in the general context of taking the issue to the 'people', but with a consciousness of the political effectiveness of existing groups which are not entirely self-interested minorities.

Within the community groups of the anti-uranium movement, there has been considerable emphasis on broadening participation and involvement in activities and campaigns. In the choice of major campaigns, a prime criterion has been the opportunity and encouragement they would provide for many people to join in. For example, leaflet distribution, signature drives, demonstrations and boycotts have been preferred over paid advertisements, statements by famous individuals, lobbying and court cases.

A strong emphasis has been put on getting people to support the movement by participating rather than with money. In particular actions such as demonstrations, efforts have been made to share out work and responsibility.

One particular area in which the question of participation is vital is that of expertise. The pro-uranium lobby has featured a few prestigious and vocal advocates who have played on the issue of expertise in nuclear matters, in particular nuclear physicist Sir Ernest Titterton and nuclear engineer Sir Philip Baxter. In responding to these 'experts', the anti-nuclear movement has relied on a number of its members who have carefully studied the issues. A few of these 'counter-experts' are nuclear scientists, but others have no special background in nuclear issues. But the main approach has not been to organise counter-expertise so as to meet the nuclear experts on their own ground, but rather to emphasise the fundamental social, political and ethical features of the nuclear issue, and to point out the values underlying the views of the pro-nuclear 'experts'. So while technical issues and expert forums have not been neglected, the main thrust of the anti-uranium movement has been on taking non-technical issues to the population at large.

Within anti-uranium groups there have been the usual range of viewpoints, political aims and preferred actions and strategies. One serious problem, fortunately encountered only in some areas, has been centralisation of decision making with accompanying disruption by sectarian groups, mainly deriving from small groups on the left. One approach which helps overcome this problem is the formation of many separate anti-uranium groups. The most successful of such groups have been those organised in suburbs in large cities and in country towns. Other groups have been formed by university students, by secondary school students, by government employees and by women.

One group of particular importance to the anti-uranium movement has been the Aborigines, especially those in the regions near proposed uranium mines. Virtually all the mines are on or near traditional Aboriginal land. This has led to the forging of a strong connection between the anti-uranium movement and the Aboriginal land rights movement. The basic opposition of Aborigines to mining on their lands - even when the compensation of large royalties has been offered - has never been in question, once they have learned the basic issues. However, local Aboriginal groups have tended to acquiesce in the face of pressures by government and mining companies. It is a cultural characteristic of the Australian Aborigines to be non-assertive, which reduces their political effectiveness in the face of ruthless, competitive, aggressive whites.

In many ways the Aboriginal issue has been one of the strongest ones for the anti-uranium movement. There has been little or nothing that can be said believably by the companies about the benefits of mining for the Aborigines. This was one reason why the government went to such unscrupulous lengths to manipulate at least the appearance of agreement by Northern Territory Aborigines to uranium mining on their tribal land, an appearance which they finally achieved in part at the end of 1978. The approach of the anti-uranium campaigners has been to emphasise the Aboriginal issue in communication and protest efforts (the theme of several major demonstrations has been "Land Rights Not Uranium") and to support local efforts to help the Aborigines oppose mining. It has not been considered useful for white anti-uranium activists to directly oppose mining on the spot in the Northern Territory, for example by occupying mining sites, although such possibilities have been analysed seriously. Telling against this tactic is the remote location of the mines from major population centres and hence the limited participation possible, and the imposition on local tribal Aborigines who might well resent major disturbance even by those who have come to 'help'. The inappropriateness of occupying mining sites seems to be a major reason why civil disobedience has played a fairly small role in the Australian anti-uranium movement.

Finally, it is worth mentioning some approaches that have not been adopted by the anti-uranium movement. One rejected approach has been appeals, based on a logically argued case, to mining company executives, political leaders and other key decision-makers. This possibility has never been considered seriously in the anti-uranium movement. The assumption (and experience) has been that logic, at least logic based on the public interest, would never prevail over vested interests.

Another unused approach - rarely has it even been discussed - has been the formation of a political party around ecological principles as in France and West Germany. One reason for this has been the strong focus on building grass-roots organisations and the rejection of hierarchical and authoritarian principles of organisation. The building of a political party requires raising finance, focussing on personalities, and a general orientation towards reform by leaders rather than through popular pressure and participation. Another reason for the neglect of the possibility for an ecology party has been the relative sympathy towards ecological goals displayed by parts of the ALP, and the difficulty which small parties have in attaining political influence under the Australian electoral system.

Finally there is the tactic of violence. This has been consciously rejected by the anti-uranium campaigners. Indeed, many have joined the movement precisely because of its emphasis on nonviolent approaches to social change. The major source of violence in the uranium 'debate' has been from governments via the police. This is especially the case in the state of Queensland, where laws against 'political' marches were passed, clearly in an attempt to subdue the anti-uranium movement.

In this section I have spelled out my conception of the strategy of the anti-uranium movement in some detail. Yet in the actual week-to-week activities of the anti-uranium campaigners, only a few people consciously have thought out a long term strategy in any detail. The assumptions about politics underlying most of the activities of the anti-uranium campaign have been for the most part unspoken. This is hardly desirable. There can be no doubt that with more attention to open, conscious political analysis and evaluation of tactics in the light of goals, anti-uranium efforts could have been made more effective.

But how is this to be achieved? Especially in the early years, the bulk of action was planned and carried out by those who above all wanted to do something, not just think about what they were going to do. The problem is a familiar one, the integration of theory and practice.

Many people outside Australia have wondered at the relative success of the Australian anti-uranium movement in mobilising public opposition to uranium mining before there were any significant nuclear fuel cycle developments in Australia. This has been compared to the overseas experience in which opposition often originates in local areas near a nuclear installation, actual or proposed. Many factors can be used to explain the relative success in mobilising people in Australia: the existence of a socially concerned section of the labour movement, epitomised by the Green Bans movement; the lack of opportunities for effective legal intervention as in the U.S. but also the lack of a heavily repressive government (except in the state of Queensland); and the wide-ranging and valuable reports of the Ranger Inquiry.

Also I think two peculiar features of the Australian situation have contributed. First, the very lack of any direct threat by nuclear power to Australians has meant that attention has focussed on wider issues such as proliferation of nuclear weapons and the effect of uranium mining on Aborigines. Grass-roots citizen movements are not primarily based on self-interest, but on moral concern. These moral issues have been prominent in the Australian nuclear debate and the anti-uranium movement has attracted activists for this reason.

Also, although uranium mining would have few direct environmental or health consequences for most Australians (except Aborigines and workers at uranium mines), there are other vitally important consequences. These include the increased emphasis on capital-intensive ventures in exporting raw materials, heavily financed by overseas capital, leading to loss of economic and political independence and a weakening of the labour movement. Such consequences have been strongly emphasised by anti-uranium campaigners, especially those in the labour movement, and have been most important in building opposition to uranium mining in key areas.

Second, the fact that uranium mining had not actually begun on any scale made the struggle seem more winnable than if, say, construction had started on a nuclear power plant. There has been also relatively little financial investment by the pro-nuclear interests and hence somewhat less ruthless efforts on their part and on their behalf by the government. This seems to be one reason why opposition to nuclear power is so strong compared to opposition to technologies which have thoroughly institutionalised themselves, such as the automobile.

In any case, the beginning of uranium mining at several deposits in early 1979 has been a strong blow to the anti-uranium movement. There has been some feeling of not knowing what to do next. The two major focusses decided upon nationally were the lobbying of trade unions and the ALP, the only groups in strategic positions to immediately stop uranium mining and export. But because lobbying efforts cannot involve large numbers of people effectively, the organised anti-nuclear movement has tended to lose direction.

Three campaigns were planned for 1979 which would provide the opportunity for such involvement: a campaign to encourage households, organisations and localities to declare regions as nuclear-free zones; a boycott of the Australia and New Zealand Bank, which has major investments in uranium mining and is the boycott target most accessible to the public; and a 'statement of defiance' signature drive which would challenge the repressive laws used to give the go-ahead for uranium mining (the powers of these laws have not yet been used, but are an obvious threat). For one reason and another, partly lack of initiative and coordination, only the nuclear-free zones campaign has achieved much success. Meanwhile, many activists have reduced activity or partially switched to other areas such as broad energy issues or environmental campaigns such as for lead-free petrol. Many others have applied their energies to more overtly political causes, such as the labour movement.

Within the anti-nuclear movement, new effort is being stimulated by possibilities for nuclear power plants in Western Australia and Victoria and for a uranium enrichment plant in South Australia or Queensland. Nationally, the umbrella group Uranium Moratorium has been superseded by Coalition for a Nuclear-Free Australia, which has a broadened membership including peace groups and some trade unions. This reflects a gradual merging of anti-uranium efforts with other issues, especially resource, environmental and peace issues.

In retrospect, there is little cause for moaning about lack of success. Several years ago the idea of leaving uranium in the ground was virtually unthinkable. Today it is, for the uranium mining companies, all too probable. Arguably, the anti-uranium movement has had already a vital effect in delaying the beginning of mining for several years. During this time economic prospects for uranium sales have sagged enormously, partly due to the international anti-nuclear movement slowing nuclear programmes. The anti-uranium movement also undoubtedly influenced the Australian government's introduction of strict uranium export conditions (which however are slowly being watered down) which are reducing sales prospects. Also highly significant are the ALP's policy stance that, once in, government, it will repudiate any prior government's commitment to uranium mining, and the opposition to uranium mining by many trade unions. These are major deterrents to uranium mining fever by companies and the government. The struggle is far from over. A lot can happen in the years before uranium export can begin in earnest.

It also seems possible that the role of the local anti-nuclear groups is now reduced, or at least changed. The anti-nuclear perspective has become institutionalised in many parts of Australian society: in trade unions, in churches, in political parties and their policies (the ALP, and the small but vocal Australian Democrats), in classrooms and in the thinking of many Australians. There is a high level of public awareness of the issues, and media coverage of both sides of the debate is significant. Individuals and groups therefore are active in many local circumstances - for example in raising awkward questions at stockholders' meetings, putting motions for nuclear free zones, or presenting ideas in classrooms - even without the direct spur of the organised anti-uranium movement. In the long run, if not the short run, this bodes well for the Australian anti-uranium struggle.

In this part, I will try to give a feeling for the detailed operation of a particular local anti-uranium group, focussing on the relation between goals and actions of the activists. The Canberra anti-uranium campaign has not been very different from campaigns in many other parts of Australia, nor does it include any highly dramatic events such as occupations and arrests or internal political struggles. But because of its fairly small size and straightforward development, I feel experiences in Canberra crystallise some of the key themes in the Australian anti-uranium movement and in grass-roots citizen action in general.

In the following I will focus on the interacting areas of issues, participation and organisation, communication and public protests.

It is my feeling that the issue of environmental hazards of nuclear power has contributed to only a comparatively small fraction of the strength of the Canberra anti-uranium movement. Few of the activists are single-minded foes of uranium mining. They realise that there are other important environmental issues, such as the burning of fossil fuels, worldwide deforestation, chemical poisons, food additives, and so forth. They are also quite aware at there are other burning issues in need of support, such as poverty, Aboriginal land rights, feminism, the nuclear arms race and US military bases in Australia, the Indonesian massacre of the East Timorese, the plight of the unemployed, and political repression. Why then devote oneself mainly to nuclear power, or devote any time to it at all?

One of the clear characteristics of a society built around nuclear power is a great centralisation of political and economic power. The enormous cost of nuclear installations, the great dangers inherent in nuclear technology due to possible environmental disasters, proliferation of nuclear weapons and criminal and terrorist threats, and the very scale and complexity of the technology mean that direct control of nuclear power by members of the public or even by representatives of the public is unlikely to be feasible. The technological complexity requires experts for attention, the economic investment leads to centralised economic control and the prevention of environmental and political hazards leads to a reduction of civil liberties. Overall, a nuclear society would be one in which democratic control over the future direction of energy policy would be greatly reduced and replaced by the prescriptions of elites and their helpers the experts, prescriptions obviously based on service to vested interests.

These points were well recognised within the Canberra anti-uranium movement from 1975 on. Many activists recognised that the anti-nuclear power struggle was not simply over environmental impact, but centred on the issue of the location of political and economic power in society. And this issue is fundamental to almost all the other major issues other than nuclear power, from feminism to the nuclear arms race. Without this understanding of the implications of nuclear power for the location of political power in society, it is likely that many of the leading anti-nuclear activists would have directed much of their effort elsewhere.

In 1975 and 1976 the major organisational base for the anti-uranium campaign in Canberra was Friends of the Earth, which devoted most of its efforts to this issue. There were weekly meetings of FOE, with attendances ranging from about 5 to 15. Who were these people? Many were university students or young unemployed people, with a scattering of people from a range of walks of life. In 1976, at the age of 29 I was often the oldest person present.

Yet these mostly young people were by no means all rank amateurs or vague high-minded idealists. Some had been involved in activist campaigns for a number of years, and as a result had a better grasp of political realities than I had ever encountered among university academics.

Moreover, the scope of activity against uranium mining was not restricted to those attending FOE meetings. In Canberra, there were a variety of people working in government bureaucracies, in scientific research organisations or at the university, teaching in schools or working through churches, unions or political parties, all who worked against uranium mining. FOE helped to focus and coordinate such people's activities, at the same time being influenced by the activities and initiatives of others. But this was not done very systematically. One of the hardest things for a citizens' movement in Canberra is maintaining communication, interaction and some degree of coordination,without manipulation or restricting initiative, among the many disparate groups and individuals sympathetic to the cause.

At the FOE meetings themselves, the main focus was on planning and carrying out activities in support of the anti-uranium campaign: making arrangements for a visiting speaker, producing leaflets, planning demonstrations and so forth. It was surprising to me (but not distressing!) how seldom the actual issues concerning nuclear power were actually raised. The bulk of the meetings were to do with the relation of tactics with goals. The goals were for the most part understood (opposition to nuclear power, and building a movement for progressive social change). The issues of nuclear power were however often raised in debating how goals were to be translated into tactics. The points to be raised in a leaflet or poster, or the choice of speakers at a rally, were discussed both in terms of what were considered the major issues relating to nuclear power and of the goals to be achieved by the leaflet or rally.

One recurrent problem was the form and status of the weekly FOE meetings. It often happened that due to the implicit agreement on goals and due to the greater familiarity of some individuals with recent developments, the meetings were off-putting for the uninitiated. The dilemma was to balance current effectiveness with measures to involve newcomers and the inexperienced. This meant balancing the need to get down to the brass tacks of who will be doing what (booking a room, doing screen printing, arranging a display) with the need for a relaxed atmosphere open for discussion. This problem has never been effectively solved.

One of the main approaches to this problem was decentralisation of decision-making and activity within FOE. Various subgroups of FOE were set up for street theatre, practice speaking, handling correspondence and the like. Furthermore, many activities naturally took a small group form, such as taking the bookstall to a shopping area for a morning. Such activities, however, still required in most cases coordination at some stage, such as the buying of books for the bookstall. The problem was that many key tasks tended to fall to the same people, such as liaison with the media, rostering people for the bookstall or making sure that all details were being looked after in planning a demonstration. Attempts were made to rotate such tasks. The problem is that few people seem to automatically take it upon themselves to handle general bureaucratic tasks, coordinate others in an activity, take responsibility for leftover details or think about the organisation of a campaign.

A second approach used to broaden the organisational base for the anti-uranium movement was to encourage the formation of separate groups. At the beginning of 1977 the Canberra Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM) was formed. It included many members of FOE but also academics, members of political parties, church people and in general a more representative cross section of the Canberra population. Since then FOE and MAUM have worked closely on the anti-uranium campaign. Other groups have been formed by students at the university, by secondary students, by government employees and by women. In other parts of Australia the most successful approach has been to form local neighbourhood groups. This has not been successful in Canberra, presumably due to its homogeneous population of mostly government employees, and due to the newness of the city and consequent lack of established neighbourhoods. Given this situation, it is not surprising that special interest groups such as students and women have been more successful.

Although the organised Canberra anti-uranium movement has not been as broadly based, decentralised and coordinated as desired by some, it is a far cry from a typical bureaucratic organisation. A large number of people have participated in activities, been involved in decision-making and in work of various types. There have been no office bearers in FOE, and even leadership of the de facto type has been mild and mostly avoided by those thrust in positions of responsibility. The entire campaign has been carried out without any paid workers.

Concerning finances, the major organisations working on the anti-uranium campaign, FOE and MAUM, at their peak of activity had a combined turnover of about $10,000 per year. The bank balance has rarely exceeded $1000. Income has come almost entirely from memberships ($10 per year) in FOE, from donations and from sales of book, badges and stickers. Expenses have been primarily for producing leaflets and posters and for buying books, badges and stickers. At a major rally, donations and sales would typically total $150, much less than expenses. The single major fund-raising event in the history of the Canberra anti-uranium movement was the 1977 Anti-Uranium Ball, which netted $3000. Needless to say, these amounts are far less than the financial muscle flexed by the pro-uranium lobby.

Communication and dissemination of information is the major purpose of many of the activities of the anti-uranium movement: production and distribution of leaflets, posters and books, letters to newspapers, press releases, formal speaking engagements, films and discussion with anyone who will partake. There have been several priorities involved in communication activities, some of which conflict: providing technically accurate information, presenting the main issues in an accessible and understandable manner, encouraging people to think and act for themselves and maximising participation in the processes. The major potential conflict to be confronted in meeting these priorities is the short term need for speaking and writing, which often falls to the more experienced and knowledgeable people, and the long term need to broaden the base of speakers and writers.

Most successful in Canberra in these respects has been the speaking programme. Formal speaking engagements have averaged up to one every fortnight or so, some arising from spontaneous requests and others being solicited. Soliciting speaking engagements is not an exciting task, often requiring more trouble than speaking itself, and so has been relatively neglected. The major audiences have been school classes, community groups (such as Rotary Clubs) and public meetings. Under the speaker-apprentice approach, at all suitable occasions an 'apprentice' speaker goes along with a more experienced or knowledgeable speaker. The latter participates as little as possible but as much as necessary in speaking and answering questions. Also there have been a number of practice and training sessions for the 'apprentices'. This approach has been successful in developing a sizeable number (about 10 over the years) of competent speakers, reducing the dependence on resident 'experts'.

Before the December 1977 federal election, a series of a dozen public meetings were arranged in country towns in the Canberra region, responding to the heightened interest in the uranium issue. These meetings included short speeches (with one apprentice), answering of questions and showing of films. These meetings clearly raised the problem of expertise versus participation in speaking. The meetings were an important opportunity for broadening participation in speaking. But since for some of the towns it would be their major first hand exposure to the anti-nuclear case, it was important to come across clearly and competently - an argument for using only the most experienced and knowledgeable speakers. A compromise was reached in using only the more prepared 'apprentices', and holding several training and practice sessions.

It seems much harder to achieve participation in writing. Most has been achieved here in writing letters to newspapers. By encouraging potential letter writers, and offering contacts for checking arguments and points of detail, quite a number of people have written a letter or two to the Canberra Times (which, unusually for Australian newspapers, prints a large fraction of letters received). Furthermore, a sizeable fraction of anti-nuclear letters have come from individuals with no direct contact with the organised anti-nuclear movement. By contrast, the pro-nuclear letter-writing has been dominated by nuclear scientists and mining company employees.

Less success has been achieved in broadening participation in the writing of articles and leaflets. Perhaps half a dozen Canberra people have written at least one article or leaflet over the years, and almost all have been academics. However, involvement and discussion has been fostered by circulating drafts of articles, leaflets and press releases to any interested person for correction and comment. Leaflets put out by FOE and MAUM, providing information only or also advertising a meeting or demonstration, need to be accepted by an appropriate meeting or other agreed upon procedure. A possible source of creative conflict arises from debate and discussion about topics covered, arguments used, political stance adopted and writing style used. I can remember long debates over whether leaflets should be short, simple and full of graphics (on the assumption that the public wouldn't read anything a little complicated or intellectual) or packed with information, although straightforward (on the assumption that the Canberra populace is relatively well educated and interested in the nuclear issues). These debates were valuable for all concerned, and helped prevent the presentation of the anti-nuclear case being monopolised by the 'counter-experts'. For me, a most important point about these discussions was that no one had any systematic evidence about the response of members of the public to different types of presentation, only a few personal experiences. The debate took place in a near vacuum of direct evidence.

Leaflets produced in Canberra are either distributed widely to advertise events (5000 to 10000 copies) or, in the case of strictly informational leaflets, distributed at bookstalls or to groups when giving talks (500 to 1000 per year per leaflet). A fraction of leaflets, and most books, come from other Australian anti-uranium groups or from overseas. In these cases, we in Canberra did not have so much choice. There is very little intergroup consultation in the production of leaflets or books.

Public protests are a form of communication also. But in protests an important component is getting people to do something which shows openly their concern on the nuclear issue. There is a big difference between privately expressing an opinion and in joining a protest march in support of a cause.

Although many demonstrations organised in Canberra were decided upon in national meetings, the final decision and most of the detailed planning was taken by the Canberra group. Several goals were implicit in the actions undertaken: making people aware of the issues, demonstrating to the public, government and other groups the existence of opposition to uranium mining, providing an experience of inspiration and solidarity for participants and providing an opportunity for participation in planning and executing the action.

Different types of actions satisfy these requirements to different degrees. Vigils, for example, provide clear testimony to others and a moving experience to participants, but if maintained for long periods usually require heavy commitments from a few individuals.

In Canberra the major public protests have been small-scale protests, large-scale demonstrations, marches and open days, and the Ride Against Uranium.

In 1975, when the Canberra anti-uranium movement was relatively small and when public concern was only small, there were fairly frequent but small demonstrations, attended mostly by the same committed individuals. By 1976 it became clear that many more people were concerned enough to attend a demonstration, but this could only be actually achieved by reducing their frequency and spending much more time on organisation and publicity. In planning, careful attention was paid to timing, to allow as many people as possible to attend: late afternoon was a typical time for a Canberra demonstration, suitable for government employees. Also important was the choice of a theme, such as Hiroshima or Aboriginal land rights. The speakers desirably were to be clear, brief, non-academic and forceful and if possible to include one or more women, Aborigines, unionists and so forth. Publicity included press releases, leaflets, posters, radio programmes and so forth. Finally there were details such as arranging for loudspeakers, contacting police, and planning for visiting speakers, bookstall, banners, announcements to be made, etc.

The principle of involving as many people as possible in preparations for demonstrations has had an impact on all these facets of organisation. In the case of publicity, the major tool has been leaflets and posters, distributed by volunteers to public noticeboards, in shops, government departments, university, schools, churches and other organisations. Over the years a sizeable contact list has been built up of individuals willing to help put up posters and leaflets. Many also volunteer or can be asked to contribute in other ways. On the other hand, the use of advertisements in newspapers has been almost entirely avoided, partly for lack of money and partly because this approach in no way builds up personal contacts and networks of interaction and help. However, decentralising the tasks of organising demonstrations has not been anywhere as complete as desired. In most cases the responsibility for much organisational planning falls by default to a few people.

The history of the Ride Against Uranium also illustrates the change in tactics resulting from the broadening of the base of the anti-uranium movement. These Rides consisted of bicyclists riding, in two main groups, from Sydney to Canberra and from Melbourne to Canberra, stopping at towns along the way for meetings and culminating in a rally in front of Parliament House in Canberra. The Rides generated publicity, demonstrated to the public the commitment felt by the riders and were a powerful experience for the riders themselves. Yet for all the success of the Rides held, it was decided to discontinue them for several reasons.

First, only some people (such as students) could participate, since the Rides lasted a week or two and required a degree of physical fitness. Second, a very large organisational effort was required. And finally, the focus on the national government was felt to be misplaced, and better redirected toward the public.

Since 1979, the organised Canberra anti-uranium movement gradually has become more diffuse, and anti-uranium activities have become more linked with other issues, in particular resource, employment and peace issues. A number of anti-uranium activists have shifted most of their energy to the unemployed workers movement and to the newly resurgent Canberra peace movement. As a consequence, the emphasis in Hiroshima Day actions since 1979 has been more on general peace issues and less on uranium, by the agreement of all concerned.

There have been no outstanding immediate developments - such as proposed nuclear power plants - to stimulate concern. But as in the case of the Australian movement as a whole, many Canberra people are continuing with anti-uranium efforts in their own situations, such as in the ALP and in government departments. In both Friends of the Earth and Canberra Peacemakers there are many new active members, a greater awareness of the importance of group process, and an increasing use of nonviolent action training. The potential exists for more concerted action on nuclear issues, but it remains to be seen whether this will be sufficient for the future.

(figures apply to the years 1976-1978 of peak activity)

Leaflet production and distribution:

Bookstalls (free leaflets; books, badges and stickers for sale) held at shopping centres, community fairs and rallies, about 25 times per year.

The Canberra Times: about 35 letters and 2 articles published per year (less than half by active FOE or MAUM members).

Formal speaking engagements: about 25 per year at schools, community groups and public meetings.

Public meetings held for visiting speakers include Amory Lovins (1975), Dale Bridenbaugh (1976), Walter Patterson (1976), Dan Ford (1977), Helen Caldicott (1979), George Wald (1979).

Lobbying (especially ALP and trade unions), involving only a few individuals (1974- ).

National leaflet, distributed mainly by letterboxing, 20000 copies (September 1976).

Signature drive, national petition against uranium mining (March-June 1977).

Series of public meetings at country towns prior to December 1977 federal election.

Nuclear free zones, encouraging households, community groups, local governments to declare areas as nuclear free zones (1979- ).

Boycott of Australia and New Zealand Bank, bank with greatest links with uranium mining (proposed for 1979, never launched).

Statement of defiance, circulation of anti-uranium petition, the signing of which potentially - but in practice very unlikely - could make signers subject to $10000 fine and 12 months gaol under Australian legislation (1980- ).

May: Ride Against Uranium: cyclists, having ridden from Sydney, Melbourne or elsewhere to Canberra, converge on Parliament House

May: Rally

June: Protest, Japanese Embassy

June: Rally

May: Ride Against Uranium

August: March and Rally, Hiroshima Day

November: 24-hour uranium discussion

December: Protest delegation to Soviet Embassy

March: Women's vigil

April: Rally

May: Ride Against Uranium

August: Rally, Hiroshima Day

August: Rally, government's decision announced

October: Rally

March: Protest, Dutch Embassy

April: Rally

August: Open day, Hiroshima Day: films, displays, discussion

December: Protest, Chinese Embassy

April: Rally

June: Protest, Philippines Embassy

August: Open day, Hiroshima Day (with Canberra Peacemakers)

August: March and Rally, Hiroshima Day (with Canberra Peacemakers)

May-August: Ride Against Uranium, followed by anti-uranium tent embassy (organised from Sydney alone)

August: Rally, Hiroshima Day (with Canberra Peacemakers)

August: Protests at 7 embassies of nuclear weapons states (with Canberra Peacemakers)

I thank David Allworth, Frank Muller, Meredith Petronella, Hugh Saddler and Rosemary Walters for helpful comments on this article, and numerous others for many valuable discussions and experiences over the years.

Desmond J. Ball, "Australia and nuclear non-proliferation", Current affairs bulletin, 55 (April 1979), pp. 16-30.

Joseph Camilleri, "Nuclear controversy in Australia: the uranium controversy", Bulletin of the atomic scientists, 35 (April 1979), pp. 40-44.

Mary Elliott (ed.), Ground for concern: Australia's uranium and human survival (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977).

Richard Graves, "Ranger: the events behind the signing of the agreement", Chain reaction, 4(2/3) (1978), pp. 46-66.

Denis Hayes, Jim Falk and Neil Barrett, Red light for yellowcake: the case against uranium mining (Melbourne: Friends of the Earth Australia, 1977)

Charles Kerr, "Perception of risk in the nuclear debate", in F. W. G. White (ed.), Scientific advances and community risk (Canberra: Australian Academy of Science, 1979), pp. 46-70.

Brian Martin, Nuclear knights (Canberra: Rupert Public Interest Movement, 1980).

Ann Mozley Moyal, "The Australian Atomic Energy Commission: a case study in Australian science and government", Search, 6 (September 1975), pp. 365-384.

Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry First Report (1976), Second Report (1977) (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service).

Alan Roberts, "The politics of nuclear power", Arena (Melbourne), No. 41 (1976), pp. 22-47.

F. P. Robotham, "The case against", in E. W. Titterton and F. P. Robotham, Uranium: energy source of the future? (Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia/Australian Institute of International Affairs, 1979), pp. 111-194.

Richard J. Roddewig, Green bans: the birth of Australian environmental politics (Montclair, New Jersey: Allanheld, Osmun & Co., 1978).

Thomas Smith, "Forming a uranium policy: why the controversy?", Australian quarterly, 51 (December 1979), pp. 32-50.

Keith D. Suter, "The uranium debate in Australia", World today, 34 (June 1978), pp. 227-235.