Reviewed by Brian Martin

Published in The Whistle (Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia), No. 109, January 2022, pp. 5-6

Tatiana Bazzichelli is an artist and activist. She is programme director of the Disruption Network Lab, based in Berlin, that promotes projects highlighting social issues, such as government surveillance. She has a special interest in whistleblowing. And she is the editor of a new book, Whistleblowing for change.

The book’s subtitle is Exposing systems of power and injustice. This is an important aspect of whistleblowing. Many whistleblowers are mainly concerned about abuses and corruption in their workplace, and want the problem to be investigated and addressed, without any wider ramifications. But there has always been another important side to whistleblowing: exposing issues to the public as part of campaigns for social change.

Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the Pentagon Papers, a revealing history of the Vietnam War, is a classic example of whistleblowing for change. So is Edward Snowden’s leak of a vast collection of documents from the National Security Agency, exposing worldwide surveillance.

Bazzichelli is primarily interested in recent activist-related whistleblowing. If this interests you, Whistleblowing for change is a must-read. It contains numerous chapters written by whistleblowers, artists, activists and journalists, plus there are interviews conducted by Bazzichelli.

The book contains six sections, each with four or five chapters. The first section, “Whistleblowing: the impact of speaking out,” is the most traditional. In it, US and UK national security whistleblowers tell their powerful stories. Billie Jean Winner-Davis provides a moving perspective as the mother of US national security whistleblower Reality Winner, who was sentenced to five years in prison.

In the second section, “Art as evidence: when art meets whistleblowing,” several artists tell how they incorporate ideas about whistleblowing into their creations. Bazzichelli twice interviewed Laura Poitras, the filmmaker Edward Snowden contacted for his disclosures, and who documented the process in the film Citizenfour. It is fascinating to learn how artists develop and express their ideas.

The theme of the third section, “Network exposed: tracking systems of control,” is surveillance. Some of the contributions are about explaining systems of surveillance, which is not whistleblowing in the legal sense but in the more general sense of communicating concerns to wider publics.

If we think of whistleblowing as telling someone in authority about a problem, it can stop as soon as the boss is informed. But when bosses and management refuse to act and close ranks, then it’s necessary to take the message outside the organisation, and the role of journalists becomes crucial in many cases, so whistleblowing and journalism are closely linked. But journalists can do only so much, and sometimes additional effort is needed to raise awareness. This is where art as evidence comes in. It is not about breaking a story but about communicating a message — one that authorities do not want to be sent — to wider audiences. Art can sometimes communicate in ways or modes different from conventional text.

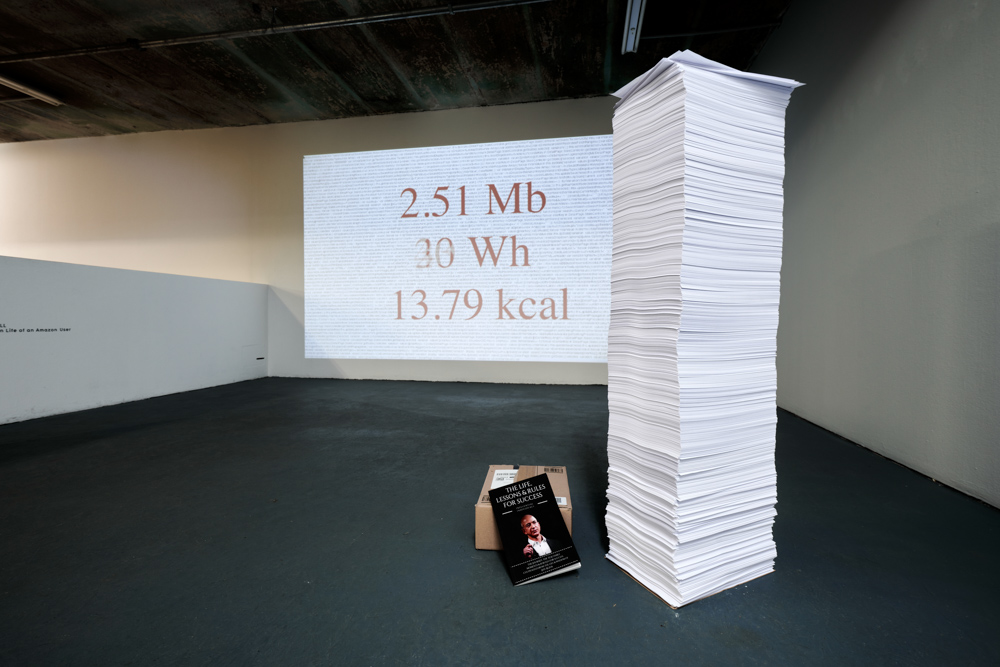

Surveillance is an issue that needs whistleblowers, such as Edward Snowden, but there are also aspects that need additional exposure, in original ways. Joana Moll has produced artworks that reveal hard-to-appreciate aspects of surveillance. In one work, The Hidden Life of an Amazon User, she downloaded all the captures of user data in a single purchase, printed them out and stacked them into an impressive pile.

The fourth section is “Uncovering corruption: confronting hidden money & power.” The most prominent exposure of secret wealth came through the Paradise Papers. An anonymous whistleblower sent vast quantities of data from the firm Mossack Fonseca to the German broadsheet Süddeutsche Zeitung. The journalists who dealt with the leak were Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer. The usual journalistic decision would have been to break the story. Bazzichelli interviews Obermaier and Obermayer about their decision to involve hundreds of other journalists from around the world in a cooperative effort to maximise the impact of the disclosures. Their efforts could be considered “journalism for change,” complementary to “whistleblowing for change.”

Christoph Trautvetter tells how groups of activists in Berlin figured out the identity of people who owned tens of thousands of apartments in the city. This was a journey through all sorts of complex financial constructs used to hide ownership. This is an example of whistleblowing in a general sense, of exposing what those who are rich and powerful want to keep secret.

The fifth section is “Exposing injustice: challenging discrimination & dominant narratives.” Daryl Davis titles his chapter, “Another type of whistleblower.” As an African American, he has spent time talking to members of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists and in many cases convinces them to renounce their racist past. He keeps a collection of Klan robes these individuals have given him. The opening of his chapter is a set of stories about white US police who have assaulted and killed blacks. We have heard of Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd, but there are many other cases. Davis is an effective change agent. Interestingly, he has been criticised by “people who look like him” for consorting with white racists.

Os Keyes’ chapter is titled “Justice, change and technology: on the limits of whistleblowing.” Its key theme is that in whistleblowing, too much reliance and attention is placed on the whistleblower and not enough on other people who are needed for anything to happen. When the whistleblower is treated as a hero, others are cast into the shadows. Keyes writes, “even truth-telling often involves multiple parties, and turning those truths into action always does.” There is enormous attention on Julian Assange and Edward Snowden, leaving others involved in WikiLeaks and the Snowden revelations, who were essential to their impact, seemingly invisible. This is a useful insight for all whistleblowers: you can’t do it alone. Building a network is essential to making a difference.

The sixth and final section is “Silenced by power: repression, isolation & persecution.” The themes here will resonate with all varieties of whistleblowers because the experience of reprisals is so common. One chapter is by Daniel Hale, a US soldier who spoke out about killings in the drone program. The chapter is his statement to the court when he was sentenced to years in prison. In his final words, he ironically apologises that his crime was for using words and not for killing other humans.

Anna Myers spent years working for the British whistleblower support organisation Public Concern at Work, now called Protect. Of all the contributors to the book, she seems to have had the greatest experience talking with whistleblowers from all walks of life and seeing the way the system fails them.

Many whistleblowers, especially the employees who report a problem within their organisation, never set out to contribute to social change. They just want the problem investigated and fixed. Yet they have much in common with campaigners challenging racism, exploitation, tax evasion and war crimes: there are problems in society, some of them systemic, and speaking out about them is part of what’s needed to address them.

Tatiana Bazzichelli

Despite the negativity of the many stories of reprisals and persecutions, the overall impact of Whistleblowing for Change is positive: whistleblowers and their supporters can make a difference. It’s important to think broadly and make connections with allies in different fields, and to learn from experience.

Download the book for free at https://www.disruptionlab.org/book, or buy a hard copy.

Brian Martin is editor of The Whistle.

Brian Martin's publications on suppression of dissent