A book review published in The Whistle (Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia), No. 64, October 2010, pp. 10-12

Sarah Westley, aged 13, was dying of cancer. In a quiet moment alone with her father Mark not long before she died, Sarah asked him to promise one thing - that no one would ever be treated the way she had been for the previous two years of her life.

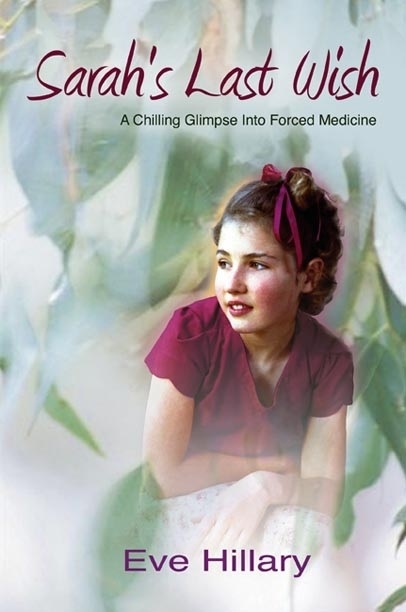

Sarah's Last Wish, a book by Eve Hillary, is the story of those two years. It is also an important step towards fulfilling Sarah's wish.

Mark and his wife Di had six children. Sarah was the third. The Westleys lived in rural New South Wales and were known in the local community as solid, hard working, sensible and family-minded. Sarah was energetic, strong-willed and a natural leader, with boundless good health and spirits. All that changed when she was 11 years old.

When Sarah suddenly became ill, her parents rushed her to the nearest hospital in their region. Rather than addressing the growth in her abdomen, the doctor suspected Sarah of being pregnant, despite her showing no signs of puberty. He contacted the NSW Department of Community Services (DOCS), a child protection agency, whose staff started probing into the Westleys' lives. Before long, DOCS staff had a secret file on the Westleys, including false information alleging they had unusual religious beliefs. In fact, they were not members of any religion.

Eventually Sarah was seen by someone who examined her physical condition, and she was rushed to surgery. The surgeon removed a huge tumour, the size of a small football. Sarah had a rare form of aggressive ovarian cancer for which the chance of survival was minimal. But her parents were not told this.

The oncologist (cancer specialist doctor) at the regional hospital told them that Sarah had an excellent chance of survival if she had aggressive chemotherapy. Mark and Di wanted to consider the options, but the oncologist did not welcome anyone questioning his plans, and before long DOCS was involved. The assumption was that if unusual religious beliefs were involved, this might mean the Westleys would oppose chemotherapy, and their resistance had to be overcome.

The story is much more complex than this. There was another oncologist involved, at a Sydney hospital, plus various DOCS workers, other health professionals, and eventually the courts. There were unending meetings and trips.

The core issue was informed choice of treatment. Sarah's parents were open to chemotherapy but they wanted to see the evidence and to consider alternatives. Their primary concern was Sarah's life, including her quality of life. However, the oncologists were determined that Sarah have aggressive chemotherapy and saw the family's concerns as evidence of resistance to be overcome at all costs. So DOCS was brought in and the nightmare continued.

The story of Sarah's experiences is harrowing. Despite repeatedly expressing that she did not want chemotherapy, and despite her parents' refusal to give consent, she was forced to have treatment, over many months. Court orders obtained by DOCS were used to overcome any opposition. The chemotherapy caused Sarah to be violently ill and reduced her to a shadow of her previous state.

At one point, the Sydney oncologist ordered an emergency operation to remove Sarah's spleen, claiming it was many times the usual size. Sarah was flown to Sydney in an air ambulance. The anaesthetist was suspicious: most patients needing an emergency splenectomy are so ill they can hardly move, but Sarah at that point was fit enough to put up a fierce resistance to the operation. The surgeon, brought in specially, cut open Sarah and removed her spleen, but was surprised to find it was normal in size. What was the emergency?

Meanwhile, DOCS used court orders to limit her family's involvement. For weeks, family members were allowed only two hours of visits or phone calls per day. Sarah was continually monitored by nursing staff and forced to eat the hospital diet. She was not permitted to eat fresh fruit or vegetables or to take vitamins.

A few of the nurses and doctors involved were kind and sympathetic to Sarah and suspected that her treatment was inappropriate and abusive, but not one was willing to challenge the oncologists or DOCS. There were no whistleblowers within the regular medical system.

Sarah in July 2003, in pain following her forced splenectomy

Enter Eve Hillary, a health practitioner and writer. Following Sarah's initial tumour surgery, her parents took her to Hillary's Integrative Health Clinic for post-operative therapy. After that Hillary and her staff were drawn into Sarah's life through the Westleys' battles with the medical establishment.

Eventually, after the Westleys had tried every legal angle to defend Sarah, they decided it was time for publicity. They approached Hillary. Could she do something? She approached various journalists, but none was willing to do anything because of the DOCS court orders. So Hillary wrote an article herself. She arranged publication in a Melbourne journal and put it on the web. Numerous readers were outraged by Sarah's treatment and before long some of them applied pressure on her oncologist, who suddenly eased the hospital's restrictions on her.

After Sarah died, Hillary, with the Westleys' support, spent several years researching what had actually happened to Sarah and how. The result was Sarah's Last Wish. It tells the story of Sarah's illness and her experiences in the medical system in a straightforward way, mainly from the point of view of Sarah's parents. As a parallel story, it describes the activities of DOCS and medical personnel involved, many of which were entirely unknown to the Westleys at the time.

Eve Hillary, author of Sarah's Last Wish

Hillary, in a reader's note at the beginning, explains how she has used documents and interviews to obtain information and then used creative licence to tell the story, including reconstructing conversations. The result is as engaging as any novel. Here is a sample conversation involving two of Sarah's sisters, Laura and Hannah, at a meal at home with their parents Mark and Di.

Hannah was impatient to see her sister [Sarah, then in hospital]. "Can we go with you Dad?" she begged. "It's creepy at the house."

Mark looked from Hannah to Laura. "What do you mean?" he asked.

Laura was about to rebuke her sister for raising the issue, since she didn't want to worry her father. But, on consideration, she thought it might be time to be up-front about what was happening to them. "I think she means, when we go to our house after school, sometimes things are in different places than they were when we left them. And some things go missing," explained Laura.

Mark put his fork down. He deliberately had not mentioned the peculiar things that had happened to him. "What kind of things go missing?" he asked.

Laura looked around the table. Almost everyone had stopped to hear what she would say. "Sometimes, your desk in the study gets messed up, Dad. And, one thing I know for sure. I'm writing to my friend about what we're all going through, and I hide the letters she writes back in a special place. The other day I noticed they were gone." (p. 142)

Hillary's narrative creates a sense of impending doom. What will happen next in the downward spiral of coercive ill-treatment? The book is aptly subtitled A Chilling Glimpse into Forced Medicine, as it is chilling indeed. It is excruciating to read about the way the honest, caring Westleys are treated by an implacable bureaucracy.

It is a consolation, in a way, to know from the very beginning that Sarah will die and her suffering will end. In the final weeks, Sarah escaped to a Melbourne hospital where she was given the supportive end-of-life treatment she needed all along, providing a dramatic contrast to the oppressive medical regime in NSW.

Sarah in July 2004, after treatment in the Integrative Health Clinic. A month later, the clinic was forced to close. After this, Sarah went downhill rapidly and died in October.

Some of my research on injustice is relevant to understanding Sarah's story. When a powerful person or group does something that others are likely to see as unfair, the perpetrator commonly uses five tactics to minimise public outrage: cover up the action; devalue the target; reinterpret the events; use official channels to give an appearance of justice; and intimidate people involved. Sarah's Last Wish provides extensive evidence that the players responsible for Sarah's coercive treatment - mainly DOCS and the two oncologists, with the legal system in support - used all five of these methods. Here are a few examples.

Cover up the action. The oncologists never provided the Westleys with Sarah's medical records, and even defied a court order that they do so. They refused to provide evidence supporting their treatments of Sarah. They hid information about Sarah's condition. Years later, government departments are still resisting FOI requests for documents about the affair.

Devalue the target. DOCS treated the Westleys as religious extremists. Sarah herself, on the basis of a misleading test, was judged as not mentally capable of making a decision about her treatment.

Reinterpret the events. The oncologists and DOCS presented themselves as defenders of proper treatment for Sarah. They lied about her health status. They treated the severe side effects of chemotherapy as insignificant.

Use official channels to give an appearance of justice. DOCS went to court repeatedly to obtain legal support for their actions. When the Westleys and others questioned Sarah's treatment, the court orders were used as justification.

Intimidate people involved. The Westleys were threatened with legal action should they not cooperate. They were subject to extensive surveillance. There was a risk that their other children - Sarah's brother and sisters - would be taken away by DOCS.

These are the same methods commonly used against whistleblowers. And what happened to Eve Hillary, the chief whistleblower about Sarah's treatment? She had set up the Integrative Health Clinic as the culmination of her vision for providing nutritional and other therapies complementary to the conventional medical treatments of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Following the clinic's involvement with Sarah's case, the authorities attacked the clinic and shut it down, leaving five staff out of work and hundreds of patients abandoned in the middle of their treatment.

To counter these five methods of inhibiting outrage, we should follow Hillary's example by using five methods to promote concern about abuses.

Expose the actions. Hillary did this with her article - it was the single most important action that changed things for Sarah. Hillary has exposed far more with Sarah's Last Wish.

Validate the target. The book shows the Westleys in an authentic light throughout, countering attempts at devaluation.

Interpret the events as an injustice. Hillary does this throughout the text. In addition, at the beginnings of chapters she provides relevant statements about medical ethics, for example "Treat your patient with compassion and respect" from the Australian Medical Association's code of ethics. These statements provide striking contrasts to the abuses perpetrated against Sarah and her family. Hillary also cites the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in support of her perspective.

Mobilise support; avoid or discredit official channels. Hillary's article triggered a huge outpouring of support, from within Australia and internationally, and changed things for Sarah. In contrast, the repeated efforts by the family to help Sarah through the courts were almost completely ineffectual.

Resist intimidation. Sarah, despite being tormented and terrified by her treatment, at times stood up to her doctors. She repeatedly protested against her forced treatment. Her parents were remarkable in continuing to do everything possible for Sarah. Hillary stood by Sarah despite the risk to her clinic.

Sarah's experiences reflect systemic problems in the NSW health system linked to counterproductive state legislation for mandatory reporting of child abuse. Reading Sarah's Last Wish, it is important to keep in mind that there are many good people in the system, including in NSW. But good intentions are not enough when the system enables the sort of abuse that Sarah suffered. Sarah's Last Wish is potent testimony to the need to bring about change so that, as Sarah wished, no one else should have to suffer the way she did.

Eve Hillary, Sarah's Last Wish, 2010. Visit http://www.sarahs-last-wish.com

Thanks to Sharon Callaghan, Don Eldridge and Jenn Phillips for valuable comments on drafts of this review.

Brian Martin is editor of The Whistle.

Suppression of dissent website