Mark Hertsgaard

A book review published in The Whistle (Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia), No. 87, July 2016, pp. 10-11

Edward Snowden is the world's most famous whistleblower. Why did he take his revelations about US government spying on citizens directly to the media rather than go through internal reporting channels? And why did he go to a freelance journalist writing for the British newspaper The Guardian rather than directly to the more prestigious New York Times?

The answer to both these questions is that Snowden observed what had happened to US national security whistleblowers before him. In particular, Snowden was influenced by the treatment of Thomas Drake, a veteran intelligence officer who raised concerns about a computer system being introduced by the National Security Agency (NSA). So here was Drake, trying to do the right thing to make the country more secure, and what happened to him? US agents went to his home and arrested him at gunpoint. He was threatened with a long prison term. He was charged under the 1917 US Espionage Act. Finally, Drake's efforts seemed to have little impact on NSA operations.

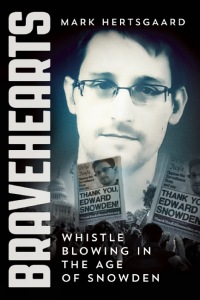

This story is recounted in Mark Hertsgaard's new book Bravehearts. Hertsgaard is a journalist and author with decades of experience, and he undertook numerous interviews for this book. He also discovered another crucial whistleblower story previously unknown to either Snowden or Drake.

The NSA, like many other government agencies, has an inspector-general, an internal body meant to deal with whistleblower disclosures. The US Congress had mandated setting up of these inspectorates. Part of the IG's duty is to protect the identity of whistleblowers.

Within the NSA inspector-general's unit was a high-level employee, John Crane, who took his job seriously. He argued long and hard on behalf of Drake, but all to no avail. Crane lost his job. Bravehearts is the first publication revealing the story of Crane. Hertsgaard calls him The Third Man.

Mark Hertsgaard

Information about NSA spying on US citizens was available to the New York Times before the 2004 presidential election. Rather than publish this dynamite story, the editors sat on it. They only published it in December 2005 because author James Risen was about to reveal everything in his book State of War.

Snowden took note. The New York Times could not be trusted to break a major story that embarrassed the government or, even worse, implicated high officials in criminality. So Snowden contacted Glenn Greenwald, a freelance journalist who wrote for The Guardian, and filmmaker Laura Poitras. Snowden's greatest fear was that his leak would have no impact. His wise choices - going directly to the media, and choosing The Guardian as the primary outlet - were based on learning from what had happened to others before him.

Part of the story of Drake involves the Government Accountability Project (GAP), the US's most prominent whistleblower advocacy organisation. Hertsgaard has long had connections with GAP, for example writing stories about whistleblowers supported by GAP. In Bravehearts, Hertsgaard provides a revealing account of the founding and development of GAP, highlighting the role of Tom Devine, for decades the key figure in the organisation. This is the most engaging treatment of GAP I've read.

Hertsgaard describes GAP's approach:

In brief: hear what a potential whistle-blower has to say; investigate the allegations rigorously ("We're a small NGO going up against rich and powerful corporations," said Clark [Louis Clark, GAP president], "so we can't afford to be wrong"); counsel the potential whistle-blower on the likely consequences of speaking out, including losing one's job, being attacked in the media, and other forms of retaliation. If the whistle-blower still wants to go ahead, seek out journalists who might report the story. Accumulate safety in numbers by alerting relevant activists, civic groups, and other possible supporters about the whistle-blower's revelations. Then press Go. (p. 72)

In a number of ways, GAP is quite different from Whistleblowers Australia. GAP has an annual budget of several million dollars whereas WBA's annual income is less than $10,000. GAP advocates on behalf of whistleblowers, using the legal system but typically harnessing the power of the media, but is highly selective in choosing cases to take up. GAP, despite its resources, can pursue only a small percentage of cases that come its way. WBA, in contrast, does not advocate on behalf of individuals but rather encourages whistleblowers to develop the skills to pursue their own cases.

Most of Bravehearts is about national security whistleblowers. Hertsgaard also discusses some other GAP campaigns, for example on nuclear power safety. His book paints as positive a picture of whistleblowing as any reader could ask for. Hertsgaard describes in simple and direct language the motivations of whistleblowers, the predictability of reprisals, the failure of official channels and the value of media coverage.

The story of John Crane, The Third Man, is important in showing that whistleblowers may have supporters within the system, yet never know it. The system as a whole is hostile to whistleblowers, to be sure, but it is worth knowing that some insiders are supportive. But do not underestimate how difficult life can be for whistleblower supporters on the inside. Even when laws seemingly protect whistleblowers, the reality may be quite different, and this is a big problem.

Devine saw the problem as systemic, rooted in power relations and the clash of institutional interests. "Whether it is a government agency or a private corporation, institutions respond to whistle-blowers with the organizational equivalent of animal instinct," he told me. "They strike back. And the scope and intensity of their retaliation is directly related to the degree of threat that the whistle-blower is perceived to pose. The more significant a whistle-blower's disclosures, the greater the perceived need to take out the threat." (pp. 135–136)

The overall message of Bravehearts is that if you want to make a difference, it is important to learn from those who went before. That's what Snowden did. Although he has paid a huge price, he has also had a huge impact, and that is something to which future whistleblowers can aspire.

Mark Hertsgaard, Bravehearts: whistle-blowing in the age of Snowden (New York: Skyhorse, 2016)

Brian Martin's publications on suppression of dissent